dimanche 30 septembre 2007

KANDINSKY, Du Spirituel dans l'art (1911)

Emil NOLDE

Emil NOLDE, Danse autour du Veau d'or, 1910, Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

Emil NOLDE, Danse autour du Veau d'or, 1910, Munich, Bayerische StaatsgemäldesammlungenHis real name was not Nolde but Hansen ; his parents were Frisian peasants. He was born in 1867 and grew up on the farm which had belonged to his mother's family for nine generations. Even as a boy Nolde was different from his three brothers: he drew, modelled and painted, and covered boards and barn doors with drawings in chalk. Some aspects of the family background, however, affected him deeply. The family were Protestants, steeped in religion, and in his youth Nolde read the Bible a great deal - its images were to return to him later in life.

It was clear that Nolde was unsuited for farm work, and in 1884 he took a job as an apprentice carver in a furniture factory in Flensburg. Here he stayed for four years, drawing and painting in his spare time. In 1888 he went to Munich, to see an exhibition of industrial arts, and managed to stay on by finding a job in a furniture factory. After only a few weeks he moved to Karlsruhe, where he found a similar job and attended classes in a school of industrial arts in the evenings. Eventually he gave up his job and enrolled in day classes at the same school, drawing from plaster casts and studying perspective and anatomy. He was unable to stay more than two semesters, as his savings ran out. In the autumn of 1889 he moved to Berlin, where he took a job as a furniture designer and spent his leisure time studying Old Master paintings in the magnificent Berlin museums; he also had his first encounters with Ancient Egyptian and Assyrian art in the archaeological collections there. In 1890 he fell ill, and spent the summer on his parents' farm.

The autumn of 1891 marked a change of direction, when Nolde saw an advertisement for a teaching post at the Museum of Industrial Arts at St Gallen in Switzerland. He applied for the job and was accepted, moving to St Gallen in January 1892. His duties were to teach industrial and ornamental drawing. The job was demanding, and he could paint only in the vacations; nevertheless, the fact that Switzerland was at the crossroads of Europe enabled him to travel. He went to Milan and saw Leonardo's Last Supper, some aspects of which were to haunt him for long afterwards, and to Vienna, where he saw Durer's prints in the Albertina. Though he was a reluctant reader, his intellectual horizons were expanding. He discovered the Symbolists and Nietzsche, and he was deeply impressed by a performance of Ibsen's The Wild Duck. Like many half-educated men, he started to feel that he was alone, misunderstood and persecuted - he was to suffer from these feelings for the rest of his life, latterly with some reason.

In 1893 Nolde embarked on an artistic enterprise which he at first treated only half seriously. He made a series of humorous postcards in which he represented the most famous of the Swiss mountains in semi-human form as a race of giants. The periodical Jugend reproduced two of these in 1896, and the proprietor of the magazine was sufficiently impressed to invite the artist to his home in Munich. Thus encouraged, Nolde borrowed enough money to issue a large edition of the postcards. They appealed to popular taste, and 100,000 copies were sold within ten days. Nolde made 25,000 gold francs, and, freed from financial worries for the time being, gave up his job and went to live in Munich. He wanted to study at the Munich Academy under the most celebrated painter in the city, Frans von Stuck, but was not accepted, and instead attended two private academies. In the autumn of 1899 he moved to Paris for nine months where he worked on and off at the Acad6mie Julian, but spent most of his time in the museums and studying the special exhibitions put on for the Paris World's Fair of 1900. He was already an admirer of Daumier's lithographs and was now impressed by Manet, but not by the other, younger Impressionists. Nolde returned to northern Germany in 1900, and embarked on a tormented search to discover his own artistic personality :

I had an infinite number of visions at this time, for wherever I turned my eyes nature, the sky, the clouds were alive, in each stone and in the branches of each tree, everywhere, my figures stirred and lived their still or wildly animated life, and they aroused my enthusiasm as well as tormented me with demands that I paint them.

Despite these feelings, Nolde painted very few visionary pictures during this period - they were to come later - but instead painted mainly landscapes and portraits. In 1900 he moved to Copenhagen, where he met and married Ada Vilstrup. They soon began to be dogged by financial problems, and in addition Ada was repeatedly ill. In the spring of 1903 the couple moved to the remote island of Alsen. In 1904 they went to Berlin, where Ada made an ill-fated attempt to make some money by singing in nightclubs. This led to a serious breakdown, so Nolde took her to Taormina in Italy to convalesce, moving afterwards to Ischia. The Italian scene, for all its beauty, did not move him as his native Germany did, and in 1905 they returned. Ada was in and out of one sanatorium after another; Nolde based himself in his lonely fisherman's cottage in Alsen. His visionary feelings were stronger than ever, the calls of animals at night had the power of suggesting colours: 'The cries appeared as shrill yellows, the hooting of owls in deep violet tones.'

He was rescued from his isolation by the young artists of Die Brücke, who recognized in him a kindred spirit. Schmidt-Rottluff saw some paintings Nolde was exhibiting in Dresden, and wrote inviting him to become a member of their group. He followed up his letter with a visit to Alsen, and in 1907 Nolde moved to Dresden, putting Ada into yet another sanatorium there. His official membership of Die Brücke did not last long - Nolde was essentially not gregarious and soon withdrew, though he maintained friendly relations with individual members. His young colleagues had an important influence on his work: in particular, he followed their example in making woodcut prints, and in addition they encouraged him to return to lithography, which he had tried in Munich.

Nolde's art became much freer: he began to see that 'dexterity is also an enemy' and he allowed himself to create fantastic paintings 'without any prototype or model, without any well defined idea ... a vague idea of glow and colour was enough. The paintings took shape as I worked.' The fantasies and the Biblical paintings he created at this time are generally considered his greatest works.

He was becoming a well known and controversial figure in the German art world of the time. In December 1910 he wrote a violently critical letter, with nationalist and racist overtones, to Max Liebermann, the greatly respected President of the Berlin Sezession, who happened to be a Jew. As a result he was expelled from the Sezession. When Max Pechstein and other Expressionists formed the Neue Sezession in the following year, Nolde duly joined, and helped to give the new organization much of its aggressive character. He was invited to take part in the second Blaue Reiter show in Munich, and also in the 1912 Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne, which brought together all the avant garde painters in Germany. In the same year the museum in Halle acquired his painting of The Last Supper despite the violent opposition of Dr Wilhelm von Bode, the great savant who had been largely responsible for building up the magnificent collection of Old Masters in Berlin.

In 1913, for reasons which remain somewhat mysterious, Nolde was offered a unique opportunity to expand his horizons. The German Colonial Office invited him to take part in an expedition to the German territories in the South Pacific. Its main purpose was medical - to study health conditions among the natives - but Nolde, who had no professional qualifications for the task, was asked to research the racial characteristics of the population. He and Ada travelled via Moscow, Mukden, Seoul, Tokyo, Peking, Nanking, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Manila and the Palau Islands to Rabaul, in German New Guinea. In 1914 he made trips to Neu Mecklenburg (now New Ireland) and the Admiralty Islands, before setting off again for home, travelling via the Celebes, Java and Aden. When Nolde and his wife arrived at Port Said they found that the First World War had broken out, and were only able to make their way home by obtaining Danish passports. On this journey Nolde noted the damage done by Europeans, even in China, which possessed such an ancient civilization of its own. 'We live in an evil era,' he said, 'in which the white man brings the whole earth into servitude.'

On his return he resumed what had now become a customary pattern, which was to spend the spring, summer and autumn in the countryside, and the winter in Berlin, where he drew rather than painted. He gave up his house on Alsen in 1916, and returned to his native Schleswig, living first at Utenwarf, which became Danish after the war. In the immediate post war years he travelled quite widely, going to England, France and Spain in 1921, and to Italy in 1924. In 1927 he settled on the German side of the frontier, building a house to his own design on the site of a disused wharf which he named 'Seebull'. His reputation now stood very high in Germany. In 1927 his sixtieth birthday was celebrated with an official exhibition in Dresden; in 1931 he became a member of the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1933 he was offered the presidency of the State Academy of Arts in Berlin.

The Nazi takeover did not effect Nolde immediately, but he had other troubles to think about. In 1934 it was discovered that he was suffering from stomach cancer. He had a successful operation in Hamburg in 1935 which was followed by a long convalescence in Switzerland, during which he met Paul Klee, who was also in poor health. The two men genuinely admired one another. Nolde once described Klee as 'a falcon soaring in the starry cosmos', and Klee reciprocated by calling him 'the mysterious hand of the lower region'.

Despite ominous signs to the contrary, Nolde had assumed that he would be immune from the Nazi campaign against Expressionism and other forms of modern art. In a certain sense the Nazi philosophy resembled his own, which continued to owe a debt to Nietzsche. He was stripped of his illusions by the events of 1937, when his work was included in the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich (his protests to the authorities went unheeded); when more than a thousand of his works were removed from German museums; and when the official celebrations for his seventieth birthday were cancelled. Worse was to follow. In 1941, the Reichskammer der Bildenden Kunste demanded that he send in his entire production for the past two years. Fifty four of the works he sent were confiscated, and he was forbidden to practise his vocation as an artist. Later Nolde went to Vienna to appeal personally to the Nazi gauleiter Baldur von Schirach - in vain.

He had already given up his apartment in Berlin, and had begun to produce what he called his 'unpainted pictures' - hundreds of small watercolours which he hid in a secret cache in his isolated house. He was very much alone. His wife became ill again in 1942 and was taken to hospital in Hamburg. The opportunity to leave Germany was long past - at one stage Nolde could have done so easily, by crossing the nearby Danish frontier, but apparently he never entertained the idea.

He survived the war, as did his invalid wife, who died in November 1946. As the grand old man of German art, Nolde now enjoyed a new lease of life. In 1947 there were exhibitions in Kiel and Lubeck to celebrate his eightieth birthday. In 1948 he married a twenty eight year old woman, the daughter of a friend. In 1952 he was awarded the German Order of Merit, his country's highest civilian decoration. He continued to work with tremendous energy, producing oils based on the watercolours he had created during the years of persecution. His last oil painting was done in 1951, and he was able to make watercolours late in 1955. Nolde died in April 1956, aged eighty eight.

samedi 29 septembre 2007

KIRCHNER II

In November 1905 Die Brücke exhibited their work - watercolors, drawings, and woodcuts - for the first time as a group at the Galerie P. H. Beyer & Sohn in Leipzig. They worked together in rented storefront studios and sought other artistic companions as well as supporters, called "passive members." Emil Nolde joined the group for a short time; among the other artists who joined were Cuno Amiet, Axel Gallen-Kallela, Otto Mueller, and Max Pechstein.

The idealism and enthusiasm of Kirchner and the other young Brucke artists can be measured by their extraordinary production. The rapid development of their personal styles was partly a result of their frenetic activity, including life drawing and painting at the Moritzburg lakes near Dresden, at the island of Fehmarn, and in their studios, as well as the production of woodcuts, lithographs, and an incredible number of drawings. In his search for an increasingly simplified form of expression, Kirchner was strongly influenced, as were his colleagues, by the art of the Oceanic and African peoples. When the group relocated to Berlin in 1910-11, Kirchner 's response to the confrontation with the metropolis resulted in the bold works that epitomize the hectic life in Berlin.

Die Brücke continued to exhibit as a group in the major German cities (Berlin, Darmstadt, Dresden, Dusseldorf, Hamburg and Leipzig) and in traveling exhibitions to smaller communities. The group's fifth annual graphics portfolio (1910) was devoted to Kirchner's work. In 1912 Die Brücke was invited to participate in the Sonderbund Exhibition in Cologne, where Heckel, Kirchner, and Schmidt-Rottluff were also commissioned to create a chapel. In that year they also exhibited in Moscow and Prague, at the second Blaue Reiter (Blue rider) show in Munich, and in Berlin at the Galerie Gurlitt. Kirchner was regarded as the leader of the group, but when in 1913 it was suggested that he compose a history of Die Brücke, the others took offense at his egocentric account, and the group broke up.

At the outbreak of the First World War Kirchner volunteered for the army, but he could not stand the discipline and constant subordination. He suffered a nervous breakdown and was temporarily furloughed and moved to a sanatorium, where he was able to complete several important paintings and the color woodcuts to illustrate Chamisso's story of Peter Schlemihl (1916). A growing dependency on Veronal (sleeping pills), morphine and alcohol did not hinder him from painting frescoes for the Konigstein Sanatorium and a number of other works.

In 1917 Kirchner moved to Switzerland, where he was supported by the collector Dr. Carl Hagemann, the architect Henri van de Velde, and the family of his physician, Dr. Spengler. He slowly recovered, while continuing to work on paintings and woodcuts. His works were exhibited in Switzerland and Germany. In 1921 he had fifty works on view at the Kronprinzenpalais (Nationalgalerie) in Berlin, which were praised by critics and established his reputation as the leading Expressionist. In 1925-26 he made his first long trip back to Germany. He stayed for a while in Dresden with his biographer, Will Grohmann, and visited the dancer Mary Wigman. His intense work on paintings, woodcuts, and sculpture expanded to include designs for the weaver Lise Guyer and, more importantly, for the decoration of the great hall of the Museum Folkwang in Essen: work never to be completed, since the Nazis seized the museum in 1933.

From 1936 onward Kirchner was increasingly disturbed by news of the Nazis' attack on modern art, occupation of Austria, and ban on the exhibition of his work in Germany. The stress of these circumstances and the onset of illness led him to destroy all of his woodblocks and some of his sculpture and to burn many of his other works. On June 15, 1938, he took his own life.

http://static.royalacademy.org.uk/files/kirchner-student-guide-13.pdf

The Brücke artist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) flouted bourgeois social conventions and sought to create a self-consciously bohemian world within the space of his studios. This photograph by Kirchner shows his studio on Körnerstraße 45 in Berlin-Steglitz. Werner Gothein (1890-1968), Kirchner’s student, and Erna Schilling (1884-1945), Kirchner’s life-partner, are seated on the bed in the background. An unknown woman in white and the Expressionist dancer Hugo Biallowons (1879-1916), who is naked, occupy the foreground. Kirchner’s painting Dodo with a Large Fan (1910) can be seen behind them.

GAUGUIN, KIRCHNER et le Primitivisme moderne

.jpg)

Paul GAUGUIN, Parau Na te Varua Ino (Paroles du Diable), 1892, 92 X 69, Washington, National Gallery of Art

Paul GAUGUIN, Parau Na te Varua Ino (Paroles du Diable), 1892, 92 X 69, Washington, National Gallery of Art***

http://www.arttattler.com/archivebridge.html

***

Gill PERRY, « The Expressive and the Expressionist », extrait de Primitivism, Cubism, Abstraction in the Early Twentieth Century, New Haven, Yale University Press :

http://www.augustana.ab.ca/files/group/612/GermanExpressionism.pdf

Hal FOSTER, « Primitive Scenes », extrait de Prosthetics Gods, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004 :

http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/chapters/0262062429chap1.pdf

Hyang-Sook KIM, table des matières de Die Frauendarstellung im Werk von Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Marburg, Tectum Verlag, 2002:

http://www.tectum-verlag.de/inhaltsverzeichnis/3828884075.pdf

vendredi 28 septembre 2007

Max PECHSTEIN

KIRCHNER - MUNCH

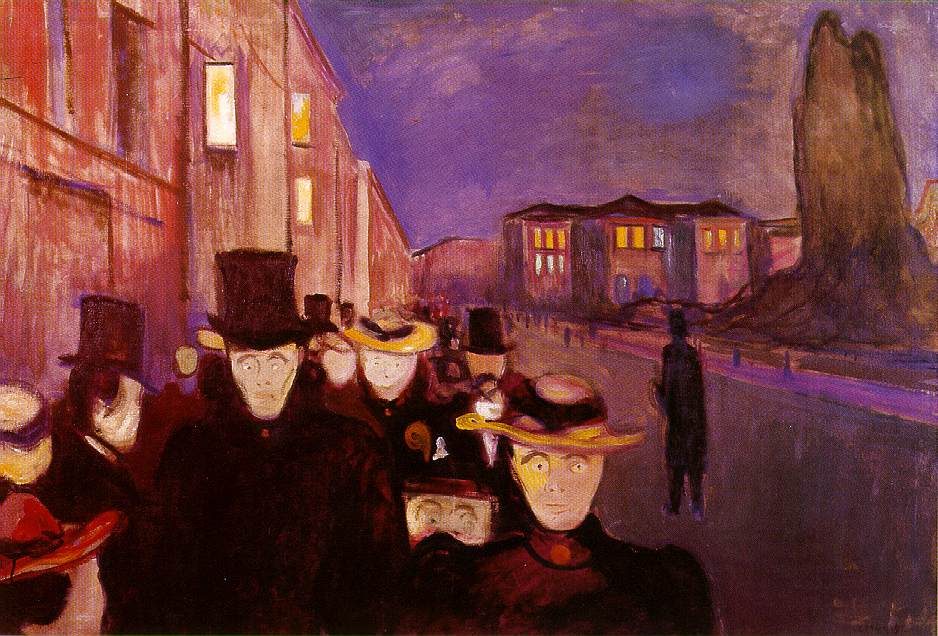

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER, Rue à Dresde, 1908, 150,5 X 200,4, New York, Museum of Modern Art

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER, Rue à Dresde, 1908, 150,5 X 200,4, New York, Museum of Modern ArtMark Daniel COHEN, « The Phenomenological Loss of the Soul » (sur l'exposition Edvard Munch : The Modern Life of the Soul, New York, MoMA, 19 Février - 19– 8 Mai 2006) :

www.nietzschecircle.com/archive_hyperion.html.

Developing in parallel with the French Fauves, and influenced by them and by the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, the German artists of Die Brücke explored the expressive possibilities of color, form, and composition in creating images of contemporary life. Street, Dresden is a bold expression of the intensity, dissonance, and anxiety of the modern city. Kirchner later wrote, "The more I mixed with people the more I felt my loneliness."

jeudi 27 septembre 2007

KIRCHNER & WHITMAN

Matthew BRADY, Portrait photographique de Walt WHITMAN, 1855

WALT WHITMAN -SONG OF MYSELF- (Paragraphe 24)

Walt Whitman am I, a Kosmos, of mighty Manhattan the son,

Turbulent, fleshy and sensual, eating, drinking and breeding ;

No sentimentalist — no stander above men and women, or apart from them ;

No more modest than immodest.

Unscrew the locks from the doors !

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs !

Whoever degrades another degrades me ;

And whatever is done or said returns at last to me.

Through me the afflatus surging and surging — through me the current and index.

I speak the pass-word primeval — I give the sign of democracy;

By God! I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.

Through me many long dumb voices ;

Voices of the interminable generations of slaves ;

Voices of prostitutes, and of deform’d persons ;

Voices of the diseas’d and despairing, and of thieves and dwarfs ;

Voices of cycles of preparation and accretion,

And of the threads that connect the stars — and of wombs, and of the father-stuff,

And of the rights of them the others are down upon ;

Of the trivial, flat, foolish, despised,

Fog in the air, beetles rolling balls of dung.

Through me forbidden voices ;

Voice of sexes and lusts — voices veil’d, and I remove the veil ;

Voices indecent, by me clarified and transfigur’d.

I do not press my fingers across my mouth ;

I keep as delicate around the bowels as around the head and heart ;

Copulation is no more rank to me than death is.

I believe in the flesh and the appetites ;

Seeing, hearing, feeling, are miracles, and each part and tag of me is a miracle.

Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touch’d from ;

The scent of these arm-pits, aroma finer than prayer;

This head more than churches, bibles, and all the creeds.

If I worship one thing more than another, it shall be the spread of my own body, or any part of it.

Translucent mould of me, it shall be you !

Shaded ledges and rests, it shall be you !

Firm masculine colter, it shall be you.

Whatever goes to the tilth of me, it shall be you!

You my rich blood! Your milky stream, pale strippings of my life.

Breast that presses against other breasts, it shall be you!

My brain, it shall be your occult convolutions.

Root of wash’d sweet flag! timorous pond-snipe! nest of guarded duplicate eggs! it shall be you !

Mix’d tussled hay of head, beard, brawn, it shall be you !

Trickling sap of maple! fibre of manly wheat! it shall be you !

Sun so generous, it shall be you !

Vapors lighting and shading my face, it shall be you !

You sweaty brooks and dews, it shall be you !

Winds whose soft-tickling genitals rub against me, it shall be you !

Broad, muscular fields! branches of live oak! loving lounger in my winding paths! it shall be you !

Hands I have taken—face I have kiss’d—mortal I have ever touch’d! it shall be you.

I dote on myself—there is that lot of me, and all so luscious ;

Each moment, and whatever happens, thrills me with joy.

O I am wonderful !

I cannot tell how my ankles bend, nor whence the cause of my faintest wish ;

Nor the cause of the friendship I emit, nor the cause of the friendship I take again.

That I walk up my stoop ! I pause to consider if it really be ;

A morning-glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books.

To behold the day-break !

The little light fades the immense and diaphanous shadows;

The air tastes good to my palate.

Hefts of the moving world, at innocent gambols, silently rising, freshly exuding,

Scooting obliquely high and low.

Something I cannot see puts upward libidinous prongs;

Seas of bright juice suffuse heaven.

The earth by the sky staid with—the daily close of their junction ;

The heav’d challenge from the east that moment over my head ;

The mocking taunt, See then whether you shall be master !

http://www.bartleby.com/142/14.html

http://www.bartleby.com/142/1.html

Walt Whitman, un cosmos, de Manhattan le fils,

Pas sentimental, pas dressé au-dessus des autres ou à l'écart d'eux

Pas plus modeste qu'immodeste.

Arrachez les verrous des portes !

Arrachez les portes mêmes de leurs gonds !

Qui dégrade autrui me dégrade

Et rien ne se dit ou se fait, qui ne retourne enfin à moi.

A travers moi le souffle spirituel s'enfle et s'enfle, à travers moi c'est le courant et c'est l'index.

Je profère le mot des premiers âges, je fais le signe de démocratie.

Par Dieu ! Je n'accepterai rien dont tous ne puissent contresigner la copie dans les mêmes termes.

A travers moi des voix longtemps muettes

Voix des interminables générations de prisonniers, d'esclaves,

Voix des mal portants, des désespérés, des voleurs, des avortons,

Voix des cycles de préparation, d'accroissement,

Et des liens qui relient les astres, et des matrices et du suc paternel.

Et des droits de ceux que les autres foulent aux pieds,

Des êtres mal formés, vulgaires, niais, insanes, méprisés,

Brouillards sur l'air, bousiers roulant leur boule de fiente.

A travers moi des voix proscrites,

Voix des sexes et des ruts, voix voilées, et j'écarte le voile,

Voix indécentes par moi clarifiées et transfigurées.

Je ne pose pas le doigt sur ma bouche

Je traite avec autant de délicatesse les entrailles que je fais la tête et le cœur.

L'accouplement n'est pas plus obscène pour moi que n'est la mort.

J'ai foi dans la chair et dans les appétits,

Le voir, l'ouïr, le toucher, sont miracles, et chaque partie, chaque détail de moi est un miracle.

Divin je suis au dedans et au dehors, et je sanctifie tout ce que je touche ou qui me touche.

La senteur de mes aisselles m'est arôme plus exquis que la prière,

Cette tête m'est plus qu'église et bibles et credos.

Si mon culte se tourne de préférence vers quelque chose, ce sera vers la propre expansion de mon corps, ou vers quelque partie de lui que ce soit.

Transparente argile du corps, ce sera vous !

Bords duvetés et fondement, ce sera vous !

Rigide coutre viril, ce sera vous !

D'où que vous veniez, contribution à mon développement, ce sera vous !

Vous, mon sang riche ! vous, laiteuse liqueur, pâle extrait de ma vie !

Poitrine qui contre d'autres poitrines se presse, ce sera vous !

Mon cerveau ce sera vos circonvolutions cachées !

Racine lavée de l'iris d'eau ! bécassine craintive ! abri surveillé de l'œuf double ! ce sera vous !Foin emmêlé et révolté de la tête, barbe, sourcil, ce sera vous !

Sève qui scintille de l'érable, fibre de froment mondé, ce sera vous !

Soleil si généreux, ce sera vous !

Vapeurs éclairant et ombrant ma face, ce sera vous !

Vous, ruisseaux de sueurs et rosées, ce sera vous !

Vous qui me chatouillez doucement en frottant contre moi vos génitoires, ce sera vous !

Larges surfaces musculaires, branches de vivant chêne, vagabond plein d'amour sur mon chemin sinueux, ce sera vous !

Mains que j'ai prises, visage que j'ai baisé, mortel que j'ai touché peut-être, ce sera vous !

Je raffole de moi-même, mon lot et tout le reste est si délicieux !

Chaque instant et quoi qu'il advienne me pénètre de joie,

Oh ! je suis merveilleux !

Je ne sais dire comment plient mes chevilles, ni d'où naît mon plus faible désir.

Ni d'où naît l'amitié qui jaillit de moi, ni d'où naît l'amitié que je reçois en retour.

Lorsque je gravis mon perron, je m'arrête et doute si ce que je vois est réel.

Une belle-de-jour à ma fenêtre me satisfait plus que toute la métaphysique des livres.

Contempler le lever du jour !

La jeune lueur efficace les immenses ombres diaphanes

L'air fleure bon à mon palais.

Poussées du mouvant monde, en ébrouements naïfs, ascension silencieuse, fraîche exsudation,

Activation oblique haut et bas.

Quelque chose que je ne puis voir érige de libidineux dards

Des flots de jus brillant inondent le ciel.

La terre par le ciel envahie, la conclusion quotidienne de leur jonction

Le défi que déjà l'Orient a lancé par-dessus ma tête,

L'ironique brocard : Vois donc qui de nous deux sera maître !

Walt WHITMAN, Paragraphe 24 de Song of Myself (Traduction d'André Gide)

HECKEL I

FRÄNZIE

http://lauratedeschiarte.blogspot.com/2011/01/ernst-ludwig-kirchner-and-new-way-of.html

DIE BRÜCKE (Résumés, conférence des 8-9 septembre 2005)

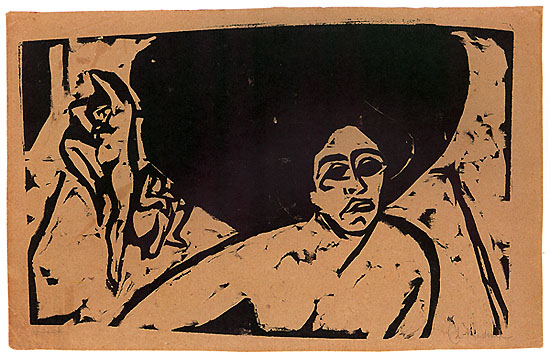

Erich HECKEL, gravure pour l'affiche de la première exposition Die Brücke à la galerie Arnold, Dresde, 1910, 16,7 X 10,9

Erich HECKEL, gravure pour l'affiche de la première exposition Die Brücke à la galerie Arnold, Dresde, 1910, 16,7 X 10,9Résumés des communications à la rencontre 1905/2005 : The Centenary of Brücke : Pioneers of German Expressionism, University of sussex, Brighton, 8-9 septembre 2005 :

http://www.sussex.ac.uk/arthistory/documents/bruecke_05_-_conference_programme.pdf

mercredi 26 septembre 2007

EXPRESSIONNISME ALLEMAND : SURVOL

Of all the "isms" in the early twentieth century, Expressionism is one of the most elusive and difficult to define. Whereas, on the one hand, Expressionism has been said to reveal its "universal character," abandoning all theories that imply a narrow, exclusive nationalistic attitude, on the other, it has been considered a "specific and familiar constant in German art for hundreds of years" (Vogt, p. 16). Scholarship has attempted to address the problematic range of the term and the contradictory emphases in its historiography. Although Expressionism did not constitute a cohesive movement or homogenous style, attention has been directed to the origins of the word and its meanings in critical discourse as well as to the contingent issues of art, society, and politics framing Expressionist avant-garde culture. Spurred on by an increasing overlap of the humanities with social, cultural, and gender studies, recent investigations reject notions of a transcendent Zeitgeist in focusing on Expressionism's interface with the public sphere.

Expressionism in Germany flourished initially in the visual arts, encompassing the formation of Künstlergruppe Brücke (Artists' Group Bridge) in Dresden in 1905 and the Blaue Reiter in Munich in 1911. The notion of the Doppelbegabung, or double talent, characterized many artists' experimentation in the different art forms, whether lyric poetry, prose, or drama. The notable precedent for this was the music-dramas of Richard Wagner and the attendant concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, which excited artists' and writers' interests in the union of the arts into a theatrical whole. Performed at the Wiener Kunstschau in 1909, Oskar Kokoschka's (1886–1980) Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen (Murderer, hope of women) is considered one of the first Expressionist plays to involve a high degree of abstraction in the text, mise en scène, sound effects, and costume. Comparatively speaking, Reinhard Sorge's (1892–1916) play Der Bettler (The beggar), written in 1910, is more discursive, though no less abstracted in relaying the metaphysical stages (Stationen) achieved by the chief protagonist, "the Poet" himself (Furness, in Behr and Fanning, p. 163). Hence, by 1914, the concept of Expressionism permeated German metropolitan culture at many levels, gaining momentum during World War I and in the wake of the November Revolution in 1918. However, any attempt to define Expressionism chronologically is as problematic as doing so in terms of style, since its influence was still felt in film after the holding of the first Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) exhibition in Mannheim in 1925.

It is telling that the kernel concept of the "expressive"—the primacy of the creative process at the expense of verisimilitude—became significant in Germany at the height of the Second Empire, corresponding to the reign of the Hohenzollern king of Prussia, Wilhelm II. The period between 1890 and 1914 was characterized by colonial expansion abroad, an unprecedented degree of urbanization and technical transformation at home, and promotion of a hide-bound national public art. Generally speaking, Expressionism grew out of late-nineteenth-century dissatisfaction with academic training and the mass spectacle of state-funded salons, the Munich (1892) and Berlin secessions (1898) withdrawing from such official or professional affiliation. In their exhibitions, the secessions fostered a sense of pluralism and internationalism, maintaining links with the art market and Paris-based Impressionism and Postimpressionism.

Within this shifting ambience between tradition and the modern, the term Expressionisten (Expressionists) was initially applied to a selection of French Fauvist and not German artists in the foreword to the catalog of a Berlin Secession exhibition, held in April 1911. Given the largely Impressionist leanings of the Secession, the collective term was a convenient way of signifying the "newest directions" in French art. Here the art of self-expression, or Ausdruckskunst as it was articulated in German, involved a degree of expressive intensification and distortion that differed from the mimetic impulse of naturalism and the Impressionist mode of capturing the fleeting nuances of the external world. This aesthetic revolt found theoretical justification in the writing of the art historian Wilhelm Worringer (1881–1965), whose published doctoral thesis Abstraktion und Einfühlung (1908, Abstraction and empathy) proposed that stylization, typical of Egyptian, Gothic, or Primitive art, was not the result of lack of skill (Können) but was propelled by an insecure psychic relationship with the external world. An impelling "will to form," or Kunstwollen, underscored art historical methodology at the time (Jennings, in Donahue, p. 89).

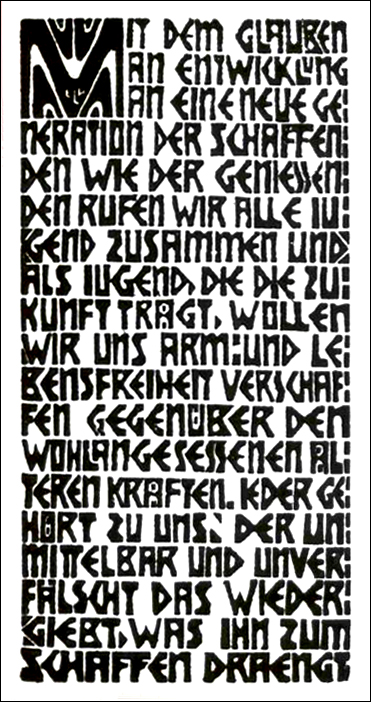

Evidently, the label Expressionism was not invented by the artists themselves but abounded in the promotional literature and reviews of current exhibitions. The proliferation of specialist journals and technological invention in publishing at the turn of the twentieth century was integral to the avantgarde's dissemination of their ideas in Expressionist literary and artistic journals, such as Der Sturm (Riot) and Die Aktion. Although the milieu encompassed a diverse political and disciplinary spectrum, commentators were united by the historical concept of Neuzeit, or modernity, "embodying a particular experiential pattern, in which it was the future that was the bearer of growing expectations" (Koselleck, p. 243). In their manifesto, members of the Brücke declared their independence from older established forces and called on all youth to look toward the future in searching for authentic expression. Similarly, in Wassily Kandinsky's (1866–1944) theoretical treatise Über das Geistige in der Kunst (1912, On the spiritual in art), he invoked the principle of "inner necessity" in postulating the evolution of art toward a utopian, transcendent form of creative expression.

Yet Expressionism was marked by a profound ambivalence toward modernity, and subject matter frequently operated between the antimonies of metropolitan alienation and the rural idyll. Both literary and artistic groups who frequented the Café des Westens in Berlin drew on the Nietzschean concept of "pathos" to convey their embrace of the dynamism of contemporary life. In emulation of the Neopathetisches Cabaret that attracted well-known poets, the painter Ludwig Meidner (1884–1966) adopted the title Die Pathetiker for his major group exhibition that was held in November 1912 at the Sturm Gallery. The city landscape was invested with elements of primal and cosmic destruction, comparable to the Bild, the word picture, which marks the Expressionist poetry of Georg Heym's (1887–1912) Umbra vitae (1912) or Jacob van Hoddis's (1887–1942) Weltende (1911, End of the world). Clearly, their utopian assumptions were compromised by a modernizing world, which was perceived as fallen and chaotic.Kulturkritik (cultural criticism) aimed to heal this tired civilization through the reference to untainted, preindustrialized and autochthonous communal traditions. Viewed through the lens of modern French painting, the Brücke artists—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel, Max Pechstein—located authenticity in old German woodcuts, African and Oceanic tribal art, which informed their carved sculpture, graphic techniques, studio interiors, and figural landscapes. In the Blaue Reiter Almanac (1912), the editors, Kandinsky and Franz Marc (1880–1916), interspersed essays on art, music, poetry, and theater with photographs of Russian and Bavarian folk art, African and Oceanic masks, and child art, seeking to legitimize the technical radicalism of modern painting through resonances with so-called primitive examples. As has been argued, primitivism was a permutation of agrarian romanticism. By the end of the nineteenth century the image of the European peasantry and nature had exhausted itself. "Nostalgia had now to cast its net wider and beyond rural Europe" (Lübbren, pp. 57–58).

Internationalism was advanced through the agencies of dealership and dispersal. The musician, writer, and dealer Herwarth Walden (1878–1941), whose Sturm Gallery was established in Berlin in 1912, displayed the works of Expressionists as well as those of Futurists and Cubists. Before and after the outbreak of war, he sent traveling exhibitions to Scandinavia, Holland, Finland, and Tokyo. As a founding member of Zurich dada, the German Poet Hugo Ball (1886–1927) provided a link between Expressionism and Dada. Ball's preoccupation with mysticism and anarchism led him to Switzerland during the war, and in a key lecture he delivered on Kandinsky (1917), he proclaimed the value of abstraction in painting, poetry, and drama to cultural regeneration.

Even in 1916, in his book Expressionismus, the art critic, novelist, and playwright Hermann Bahr (1863–1934) remained warmly disposed toward Picasso and French art since Manet. Bahr was writing at a time when Germany had suffered staggering reversals on the battlefield and disillusionment had set in with mechanized warfare of a kind that no one had imagined. Fiercely antitechnological and antibourgeois, he characterized the era as a "battle of the soul with the machine," articulating the desire for a prelapsarian state of innocence (p. 110). In 1917 literary Expressionism came of age with Kasimir Edschmid's (1890–1966) manifesto Über den Expressionismus in der Literatur und die neue Dichtung, strengthening the emphasis on Schauen, or "visionary experiences," rather than on Sehen ("observation of visual details") (Weisstein, p. 207). Given its emphasis on spiritual values, the literary critic Wolfgang Paulsen would have labeled this genuine Expressionism so as to distinguish it from Activist Expressionism, deriving from the lineage of Karl Marx. However, not all socialism ran counter to the notion of "spiritual revolution" and, according to Rhys Williams, Georg Kaiser's (1878–1945) play Von morgens bis mitternachts (1916, From morn to midnight) can be read as a "dramatization of [Gustav] Landauer's indictment of capitalism" and the search for the verbindender Geist (unifying spirit) that he advocated (Behr and Fanning, pp. 201–207).

In Berlin, the organization Novembergruppe was founded. It called on all Expressionists, Futurists, and Cubists to unite under the banner of cultural reform and reconstruction. Although initially attracting dadaists to its ranks, the equation between Expressionism and radicalism became more difficult to sustain within the stabilization of order brought about by the Weimar government. Due to democratization and to pressure exerted by various artists' councils, Expressionism made inroads into the public sphere and was avidly collected by major museums throughout Germany. Moreover, well-known Expressionists such as Kandinsky and Paul Klee (1879–1940) were approached to teach at the Bauhaus in Weimar, founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius (1883–1969). This school was based on socialist and utopian principles that placed artists at the center of a new kind of design that served modern society. Though Kandinsky sustained his belief in the expressive and mystical values of art, he abandoned the expressive abstraction of the Munich years and explored geometric formal elements in a more systematic manner.

However, the death knell of Expressionism, according to many commentators, lay in its commercialization and consequent loss of authenticity. It was considered debased in losing its soul to mass culture. In the early twenty-first century, scholars tend to regard the ability of Expressionism to adapt to the demands of technological advancement as a measure of its success. The silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, directed by Robert Wiene (1881–1938), was released in Berlin in 1920 and achieved resounding international acclaim. Fritz Lang's (1890–1976) Metropolis (1927) and Josef von Sternberg's (1894–1969) The Blue Angel (1930) appeared after Expressionism's demise and Georg Wilhelm Pabst's (1885–1967) Pandora's Box in 1928.

During the 1930s, the polarization in German politics and society led views on the left and the right to target Expressionism. From a position of exile in Moscow, the Marxist theoretician Georg Lukács (1885–1971) launched an attack in his essay "'Größe und verfall' des Expressionismus" (1934; Expressionism: its significance and decline, Washton-Long, pp. 313-317). Favoring a form of typified realism that was deduced from nineteenth-century literary sources, Lukács considered Expressionism the product of capitalist imperialism. According to this model, its subjectivity and irrationalism would inevitably lead to fascism. Debates ensued in the émigré literary journal Das Wort, the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch (1885–1977) vigorously defending the role of autonomous experimentation in the visual arts in his essay "Diskyssion über Expressionismus" (1938; Discussing Expressionism, Washton-Long, pp. 323–327). In post-1945 historiography, critics tended to lose sight of Bloch's salvaging of the utopian and communal aspirations of Expressionism.

Interestingly, even after the Nazis assumed power in 1933, there was rivalry between the antimodernist Alfred Rosenberg (1893–1946) and the Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945), who considered Expressionism and the works of Emil Nolde (1867–1956) to be uniquely German. Indeed, Goebbels's novel Michael adopted the declamatory style and format of the Expressionist stationendrama in tracing the journey of the eponymous hero from soldier to Nazi superman (1929). In 1934, Rosenberg's appointment as spiritual overseer of the National Socialist Party sealed the fate of the avant-garde. Official confiscation of works from public collections accompanied the dismissal of Expressionists, left-wing intellectuals, and Jews from prominent positions in the arts.

In 1937, moreover, the infamous exhibition "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate art) was inaugurated in Munich, signaling the Third Reich's devastating efforts to expunge Expressionism's claim to cultural status. Expressionism underwent transformation in exile as refugee artists, writers, and filmmakers reexamined their cultural identity in light of the demands of their adoptive countries. Others were not as fortunate. Kirchner resided in Switzerland since 1917, and his frail psychological state was exacerbated by the pillaging of 639 of his works from museums and by the inclusion of thirty-two in the "Entartete Kunst" exhibition. He committed suicide in 1938. The poet Van Hoddis, who was of Jewish origin and suffered mental disorders for many years, was transported to the Sobibor concentration camp in 1942, the exact date of his murder being unrecorded.

Shulamith BEHR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

PRIMARY SOURCES

SECONDARY SOURCES

Barron, Stephanie, ed. Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-garde in Nazi Germany. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1991.

mardi 25 septembre 2007

EXPRESSIONNISME ALLEMAND

Franz MARC, Kampfende Formen (Combat de formes), 1914, 91 X 131, Munich, Staatsgalerie moderner Kunst

Franz MARC, Kampfende Formen (Combat de formes), 1914, 91 X 131, Munich, Staatsgalerie moderner KunstHAR-14395

Louis Lefrançois

Objectifs :

L’EXPRESSIONNISME ALLEMAND est un cours de second niveau dont l’objectif principal est de familiariser ses participants avec les pratiques et les problèmes, les acteurs, les thèmes et les débats qui ont orienté les développements contradictoires des diverses tendances du courant expressionniste dans l’art et la culture modernes entre 1905 et 1937. Le cours se donne pour tâche de présenter et d’interpréter historiquement les différentes manifestations de l’expressionnisme et d’analyser les composantes fondamentales de cet effort artistique qui entendait bouleverser les normes de la civilisation bourgeoise au moyen de la réévaluation agressive du primitif, de l’exaltation de l’intériorité poétique et de la promotion des qualités les plus subjectives de la révolte morale. Le cours vise également à définir les bases d’une compréhension historique des pratiques culturelles, et à favoriser la formation d’un jugement critique cohérent.

Contenu :

Le cours EXPRESSIONNISME ALLEMAND aborde l’émergence, la conjugaison et le développement conflictuel des stratégies mises en œuvre par les différents protagonistes et tendances du courant expressionniste pour bouleverser les conventions dominantes de la société industrielle et ainsi fonder sur des bases neuves la pratique de la créativité subjective. Le cours se donne pour tâche d’examiner, à partir de l’étude des documents produits par les expressionnistes (peintures, gravures, sculptures, revues, expressions poétiques dans les domaines de la littérature, du théâtre, de la musique, de la photographie, du design et du cinéma, actions politiques), les principales expériences qui ont caractérisé l’intervention expressionniste ; celle-ci étant considérée à la fois comme courant poétique singulier, englobant plusieurs tendances opposées, et comme moment particulier de l’histoire des avant-gardes historiques. Le cours accorde une attention toute particulière aux questions relatives à la formation du concept d’« expressionnisme », aux relations que ce courant a entretenu avec les grandes tendances de l’innovation artistique moderne et de l’avant-garde historique (les « Fauves », le modernisme viennois, le cubisme, le futurisme, DADA, le constructivisme) ainsi qu’à l’héritage poétique et philosophique qu’il a hautement revendiqué (de Van Gogh et Gauguin à Nietzsche et Freud, de Munch et Ensor à Thoreau, Whitman et Strindberg)

Parmi les principaux thèmes, problèmes et sujets qu’aborde le cours, nous discuterons notamment : de la formation historique et des expériences poétiques menées par les principaux groupes « expressionnistes » : Die Brücke, Der Blaue Reiter, Der Sturm et Die Aktion ; de l’affirmation artistique et théorique du primitif ; de la situation de l’« abstraction » dans le champ des recherches expressionnistes ; de l’importance du projet d’œuvre d’art totale ; de l’impact de la Première Guerre mondiale et de la Révolution de novembre 1918 sur la redéfinition en profondeur de l’expressionnisme en Europe ; du tournant opéré par DADA ; du déploiement du vérisme critique et de la Nouvelle Objectivité ; de l’introduction et de la consolidation du style expressionniste au cinéma ; de la transformation des apports issus de l’expressionnisme dans l’expérience du Bauhaus ; et de la liquidation officielle de l’expressionnisme par la politique culturelle du national-socialisme.

Démarche :

Exposés magistraux accompagnés de projection de diapositives. Lecture et étude de textes. Présentation de films et de documents audio-visuels.

Évaluation :

Deux examens-maison comptant chacun pour 50% de la note finale.

Bibliographie sélective

Ades, Dawn, Photomontage, Paris, Chêne, 1976

Ades, Dawn, The Twentieth Century Poster : Design of the Avant-Garde, New York, Walker Art Center 1984

Adorno, Theodor W., Quasi una Fantasia, Paris, Gallimard, 1982

Adorno, Theodor W., Sur quelques relations entre musique et peinture, Paris, La Caserne, 1995

Almanach du Blaue Reiter (1912), Paris, Klincksieck, 1981

Amengual, Barthélemy, « 1918-1926 : l’expressionnisme allemand », CinémAction, no55, avril 1990

Anders, Günther, George Grosz, Paris, Allia, 2006

Aragon, Louis, La Peinture au défi, Paris, Hermann, 1965

Argan, Giulio Carlo, Walter Gropius et le Bauhaus, Paris, Denoël-Gonthier, 1979

Aron, Jacques, Anthologie du Bauhaus, Bruxelles, Devillez, 1995

Arp, Jean (Hans), Jours effeuillés, Paris, Gallimard 1966

Arendt, Hannah, Le Système totalitaire, Paris, Seuil, 1972

Arendt, Hannah, L’Impérialisme, Paris, Fayard, 1982

Arendt, Hannah, La Nature du totalitarisme, Paris, Payot, 1990

Aynsley, Jeremy, Graphic Design in Germany 1890-1945, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000

Bablet, Denis et J. Jacquot (éds.), L’Expressionnisme dans le théâtre européen, Paris, C. N. R. S., 1971

Bablet, Denis (éd.), L’Oeuvre d’art totale, Paris, C. N. R. S., 1995

Baechler, Christian, L’Allemagne de Weimar 1919-1933, Paris, Fayard, 2007

Ball, Hugo, La Fuite hors du temps, Monaco, Éditions du Rocher, 1993

Baqué, Dominique, Les Documents de la modernité. Anthologie de textes sur la photographie de 1919 à 1939, Nîmes, Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, 1993

Barron, Stephanie et Wolf-Dieter Dube, German Expressionism. Art and Society 1909-1923, London, Thames & Hudson, 1997

Barron, Stephanie, German Expressionist Sculpture, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County art Museum, 1983

Barron, Stephanie,German Expressionism, 1915-1925 : The Second Generation, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, County Museum of Art, 1988

Barron, Stephanie, « Degenerate Art » : The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, New York, Harry H. Abrams, 1991

Bartov, Omer, Mirrors of Destruction : War, Genocide and Modern Identity, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000

Beaupré, Nicolas, et alii (éds), 1914-1945 : L’Ère de la guerre, Paris, Agnès Viénot, 2004

Beckmann, Max, Écrits, Paris, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2002

Béhar, Henri et Michel Carassou, Dada. Histoire d’une subversion, Paris, Fayard, 1990

Behr, Shulamith, Expressionism, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1999

Behr, Shulamith, Women Expressionists, New York, Rizzoli, 1988

Behr, Shulamith, David Fanning & Douglas Jarm (éds.), Expressionism Reassessed, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1993

Benjamin, Walter, Oeuvres I : Mythe et violence, Paris, Denoël, 1965

Benjamin, Walter, Oeuvres II : Poésie et Révolution, Paris, Denoël, 1965

Benn, Gottfried, Un Poète et le monde, Paris, Gallimard, 1965

Benn, Gottfried, Double vie, Paris, Minuit, 1981

Benson, Timothy O. (éd.), Between Worlds : A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, 1910-1930, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2002

Benson, Timothy O. (éd.), Central European Avant-Gardes : Exchange and Transformation, 1910-1930, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2002

Berg, Alban, Écrits, Paris, Bourgois/Seuil, 1984

Berman, Marshall, All That Is Solid Melts Into Air : The Experience of Modernity, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1982

Bloch, Ernst, L’Esprit de l’utopie, Paris, Gallimard, 1977

Bloch, Ernst et alii, Aesthetics and Politics, London, Verso, 2007

Bloess, Georges, Voix, regard, espace dans l’art expressionniste, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1998

Bonnet, Jean Claude et alii, « La Génération expressionniste », Cinématographe, no 22, décembre 1976

Boorman, Helen, « Rethinking the Expressionist Era : Wilhelmine Cultural Debates and Prussian Elements in German Expressionism », Oxford Art Journal, 9/2, 1986

Boulez, Pierre, Paul Klee, le pays fertile, Paris, Gallimard, 1989

Bowlt, John E., « Wassily Kandinsky : The Russian Connection », in John E Bowlt et Rose-Carol Washton-Long, The Life of Kandinsky in Russian Art. A Study of ‘’On the Spiritual in Art’’, Newtonville, Oriental Research Partners, 1980

Bradley, William S., Emil Nolde and German Expressionism : A Prophet in his Own Land, Ann Arbor, UMI Research Press, 1986

Brecht, Bertolt, Sur le réalisme, Paris, L’Arche, 1970

Brecht, Bertolt, Écrits sur la politique et la société, Paris, L’Arche, 1977

Bridgwater, Patrick, « The Expressionist Generation and Van Gogh », New German Studies, volume 8, 1987

Brion-Guerry, Lilianne (éd.), L’Année 1913. Les formes esthétiques de l’œuvre d’art à la veille de la Première Guerre mondiale, Paris, Klincksieck, 1971-1973, 3 volumes

Broch, Hermann, Création littéraire et connaissance, Paris, Gallimard, 1966

Broch, Hermann, Quelques remarques à propos du Kitsch, Paris, Allia, 2001

Bronner, Stephen Eric et Douglas Kellner, Passion and Rebellion. The Expressionist Heritage, New York, Columbia University Press, 1988

Brougher, K & J. Zilczer (éds.), Visual Music : Synesthesia in Art and Music since 1900, Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005

Bürger, Peter, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1984

Calinescu, Matei, Five Faces of Modernity : Modernism, Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism, Durham, Duke University Press, 1987

Cernuschi, C., « Oskar Kokoschka and Sigmund Freud : Parallel Logics in the Exegetical and Rhetorical Strategies of Expressionism and Psychoanalysis », Word & Image, 15/4, 1999

Charle, Christophe, La Crise des sociétés impériales : Allemagne, France, Grande-Bretagne 1900-1940, Paris, Seuil, 2001

Clark, T. J., Farewell to an Idea, Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1999

Clair, Jean (éd.), Les Réalismes 1919-1939, Paris, Musée National d’Art moderne, 1981

Clair, Jean (éd.), Vienne 1880-1933. L’Apocalypse joyeuse, Paris, Musée National d’Art moderne, 1986

Clerbois, Sébastien et Catherine Verleysen, Dictionnaire culturel de l’expressionnisme, Paris, Hazan, 2002

Cork, Richard, A Bitter Truth : Avant-Garde Art and the Great War, New Haven, Yale University Press,1994

Craig, Gordon, Germany 1866-1945, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997

Dachy, Marc, Journal du mouvement dada. 1915-1923, Genève, Albert Skira, 1989

Dachy, Marc, Dada & les dadaïsmes. Rapport sur l’anéantissement de l’ancienne beauté, Paris, Gallimard, 1994

Demange, Camille, « L’Expressionnisme allemand et le mouvement révolutionnaire » in Jean Jacquot, Le Théâtre moderne : Hommes et tendances, Paris, Éditions du C. N. R. S., 1958

Deutsche, Rosalyn, « Alienation in Berlin : Kirchner’s Street Scenes », Art in America, 71/1, January 1983

Döblin, Alfred, L’Assassinat d’une renoncule et autres nouvelles, Grenoble, P. U. G., 1984

Döblin, Alfred, Berlin Alexanderplatz, Paris, Gallimard, 1981

Döblin, Alfred, Novembre 1918, Paris, Quai Voltaire, 1990-1992, 3 tomes

Donahue, Neil H. (éd.), Invisible Cathedrals : The Expressionist Art History of Wilhelm Worringer, University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995

Donahue, Neil H, A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism, Rochester, Camden House, 1999

Dube, Wolf-Dieter, Les Expressionnistes, Paris, Éditions Thames & Hudson, 1996

Dube, Wolf-Dieter, Journal de l’expressionnisme, Genève, Skira, 1983

Dufour-Kowalska, Gabrielle, Emil Nolde : L’Expressionnisme devant Dieu, Paris, Klincksieck, 2007

Dupeux, Louis, Histoire culturelle de l’Allemagne, Paris, P. U. F., 1989

Edwards, Steve & Paul Wood, Art of the Avant-Gardes, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004

Egbert, Donald Drew, « The Idea of Avant-Garde in Arts and Politics », American Historical Review, 73, 1967, 339-366

Eichenlaub, René, Ernst Toller et l’expressionnisme politique, Paris, Klincksieck, 1977, 2 tomes

Eichenlaub, René, « L’Expressionnisme allemand et la Première Guerre mondiale. À propos de l’attitude de quelques-uns de ses représentants », Revue d’Histoire moderne et contemporaine, vol.30, 1983

Einstein, Carl, Bébuquin, ou les Dilettantes du miracle, Paris, Samuel Tastet, 1987

Eisner, Lotte, L’Écran démoniaque, Paris, André Bonne, 1952

Eisner, Lotte, Fritz Lang, Paris, Flammarion, 1988

Eisner, Lotte, Murnau, Paris, Ramsay, 1987

Elderfield, John, Kurt Schwitters, London, Thames & Hudson, 1985

Elger, Dietmar, L’Expressionnisme. Une révolution artistique allemande, Cologne, Taschen, 1994

Ernst, Max, Écritures, Paris, Gallimard, 1970

Ettlinger, L. D, « German Expressionism and Primitive Art », The Burlington Magazine, 110/781, April 1968

Expressionnisme, L’Arc, no25, 1964

Expressionnisme européen, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1970

Fauchereau, Serge, Expressionnisme, Dada, Surréalisme et autres ismes, Paris, Denoël, 2001

Forgacs, Eva, The Bauhaus Idea and Bauhaus Politics, London, Oxford University Press, 1997

Fiedler, Jeannine (éd.), Photography at the Bauhaus, London, Dirk Nishen, 1990

Figures du moderne : L’Expressionnisme en Allemagne 1905-1914 : Dresde, Munich, Berlin, Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1992

Filler, Martin, « Fantasms and Fragments : Expressionist Architecture », Art in America, 71/1, January 1983

Franciscono, Marcel, Walter Gropius and the Creation of the Bauhaus in Weimar, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1971

Gamard, Elizabeth B., Kurt Schwitters Merzbau : The Cathedral of Erotic Misery, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2000

Gangl, Manfred et Hélène Roussel (éds.), Les Intellectuels et l’État sous la République de Weimar, Rennes, Centre de recherche Philia, 1993

Gasser, Étiennette, « Sur les origines du terme ‘’Expressionnisme’’ », Revue d’Esthétique, 22/4, 1969

Gay, Peter, Le Suicide d’une République : Weimar 1918-1933, Paris, Calmann-Levy, 1993

Geelhar, Christian, Paul Klee et le Bauhaus, Neuchâtel, ides et Calendes, 1972

Glicksohn, Jean-Michel, L’Expressionnisme littéraire, Paris, P. U. F., 1990

Godé, Maurice, Der Sturm et Herwarth Walden ou l’utopie d’un art autonome, Nancy, Presses Universitaires de Nancy, 1990

Goldwater, Robert, Le Primitivisme dans l’art moderne, Paris, P.U.F., 1988

Gordon, Donald E., « On the Origin of the Word ‘’Expressionism’’ », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 29, 1966

Gordon, Donald E., Expressionism : Art and Idea, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987

Greenberg, Allan C., Artists and Revolution : Dada and the Bauhaus, Ann Arbor, UMI Research, 1980

Gross, Otto, Révolution sur le divan, Paris, Solin, 1992

Grosz, George, Un petit oui et un grand non, Nîmes, Jacqueline Chambon, 1990

Haas, Patrick de, Cinéma intégral. De la peinture au cinéma dans les années vingt, Paris, Transédition, 1985

Hademann, Paul, « Parallélismes de démarche et de structure dans l’expressionnisme artistique et littéraire », Publications de l’Institut de formation et de recherche en littérature, 4, 1979

Hademann, Paul, « Musique et espace chez Kandinsky. À propos du Spirituel dans l’art », Musique et société, Bruxelles, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 1988

Haftmann, Werner, Painting in Twentieth Century, London, Lund Humphries, 1965

Hahl-Fontaine, Jelena, Kandinsky, Bruxelles, Marc Vokar Éditeur, 1993

Hausmann, Raoul,Courrier Dada, Paris, Allia, 1992

Hausmann, Raoul, Hourra ! Hourra ! Hourra !, Paris, Allia, 2004

Hausmann, Raoul, Sensorialité excentrique, Paris, Allia, 2005

Haxthausen, C. W. & H. Suhr (éds.), Berlin : Culture and Metropolis, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1990

Heller, Reinhold (éd.), Art in Germany 1909-1936 : From Expressionism to Resistance, Milwaukee, Milwaukee Art Museum, 1990

Heller, Reinhold, Gabriele Münter : The Years of Expressionism, 1903-1920, New York, Prestel, 1997

Henry, Michel, Voir l’invisible. Sur Kandinsky, Paris, P. U. F., 2005

Herf, Jeffrey, Reactionary Modernism. Technology, Culture and Politics in Weimar and the Third Reich, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984

Hinz, Berthold, Art in the Third Reich, New York, Pantheon Books, 1979

Hommage à Kandinsky, XXe siècle, numéro spécial, 1974

Horkheimer, Max et T. W. Adorno, Dialectique de la Raison, Paris, Gallimard, 1974

Huelsenbeck, Richard, Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, New York, Viking Press, 1974

Huelsenbeck, Richard (éd.), Almanach Dada, Paris, Champ Libre, 1980

Huelsenbeck, Richard, En avant Dada ! L’Histoire du dadaïsme, Paris, Allia, 1983

Huelsenbeck, Richard & George Grosz, Doctor Billig, Paris, Fourbis, 1993

Hulten, Pontus (éd.), Paris-Berlin, Paris, Musée National d’Art moderne, 1978

Jähner, Horst, Die Brücke. Naissance et affirmation de l’expressionnisme, Paris, Cercle d’art, 1992

Johnston, William M., L’Esprit viennois. Une histoire intellectuelle et sociale 1848-1938, Paris, P. U. F., 1985

Jung, Franz, Le Scarabée-torpille : Considérations sur une grande époque, Paris, Ludd, 1993

Junod, Philippe, « Synesthésies, correspondances et convergence des arts : un mythe de l’unité perdue ? », Kunst Musik und Schauspiel, numéro 2, 1983

Kaes, Anton, Martin Jay & Edward Dimendberg (éds.), The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994

Kafka, Franz, Récits. Romans, Journaux, Paris, Librairie générale française, 2000

Kandinsky, Wassily, Du Spirituel dans l’art, Paris, Denoël, 1989

Kandinsky, Wassily, Regards sur le passé et autres textes, 1912-1922, Paris, Hermann, 1990

Kandinsky, Wassily, Écrits complets, Paris, Denoël-Gonthier, 1970, 3 volumes

Kandinsky, Wassily, Klänge (édition bilingue), Paris, Bourgois, 1987

Kandinsky, Wassily, Du théâtre, Paris, Adam Biro, 1998

Karcher, Eva, Otto Dix, Cologne, Taschen, 1989

Karl, Frederick, Modern and Modernism : The Sovereignty of the Artist, New York, Atheneum, 1985

Kessler, Frank, « Les Architectes-peintres du cinéma allemand muet », Iris, no12, 1991

Klee, Paul, Journal, Paris, Grasset, 1959

Klee, Paul, Théorie de l’art moderne, Paris, Denoël-Gonthier, 1975

Klee, Paul, Écrits sur l’art, Paris, Dessain & Tolra, 1977

Kokoschka, Oskar, « Edvard Munch’s Expressionism », College Art Journal, X, 1950

Kokoschka, Oskar, Mirages du passé, Paris, Gallimard, 1984

Kokoschka, Oskar, My Life, New York, Macmillan, 1974

Kracauer, Siegfried, De Caligari à Hitler, Lausanne, L’Age d’Homme, 1973

Kracauer, Siegfried, The Mass Ornement, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1995

Kraus, Karl, Dits et contredits, Paris, Champ Libre, 1975

Kraus, Karl, La Boîte de Pandore, Ludd, 1985

Kraus, Karl, Pro Domo et Mundo, Paris, Éditions Gérard Lebovici, 1985

Kraus, Karl, La Nuit venue, Paris, Éditions Gérard Lebovici, 1986

Kraus, Karl, Les Derniers jours de l’humanité, Rouen, Éditions de l’Université de Rouen, 1986

Kubin, Alfred, L’Autre Côté, suivi de Autobiographie, Paris, Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1964

Kubin, Alfred, Le Cabinet de curiosités et autres textes, Paris, Allia, 1998

Kubin, Alfred, Le Travail du dessinateur, Paris, Allia, 1999

Kubin, Alfred, Histoires burlesques et grotesques, Paris, Phébus, 2006

Kupka, Frantisek, La Création dans les arts plastiques (1923), Paris, Cercle d’Art, 1989

Kurz, Rudolf, Expressionnisme et cinéma (1926), Grenoble, P. U. G., 1987

Lampert, Catherine (éd.), Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism in the Twenties, London, Hayward Gallery, 1978

Laqueur, Walter, Weimar. Une Histoire culturelle de l’Allemagne des années 20, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1978

Lasker-Schüler, Else, Poésie complète, Paris, Fourbis, 1994

Lasko, Peter, The Expressionists Roots of Modernism, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2003

Lavin, Maud, Cut with the Kitchen Knife. The Weimar Photomontage of Hannah Höch, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993

Lemoine, Serge, Vienne 1900. Klimt, Schiele, Moser, Kokoschka, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2005

Leni, Paul, « L’Image comme action », Cinématographe, no75, février 1982

Le Rider, Jacques, Modernité viennoise et crise de l’identité, Paris, P. U. F., 1990

Lethen, Helmut, Cool Conduct : The Culture of Distance in Weimar Germany, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2002

Levine, F. S., The Apocalyptic Vision : The Art of Franz Marc as German Expressionist, New York, Harper & Row, 1979

Lewis, Beth Irwin, George Grosz. Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1971

Lindqvist, Sven, Maintenant tu es mort : Le Siècle des bombes, Paris, Le Serpent à plumes, 2002

Lissitzky-Küppers, Sophie, El Lissitzky. Life, Letters, Texts, London, Thames & Hudson, 1968

Lista, Marcella, L’Oeuvre d’art totale à la naissance des avant-gardes 1908-1914, Paris, Éditions du C. T. H. S., 2006

Lloyd, Jill & Magdalena M. Moeller, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner : The Dresden and Berlin Years, London, Royal Academy of Arts, 2003

Lloyd, Jill, German Expressionism : Primitivism and Modernity, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1991

Lloyd, Jill, Van Gogh et l’expressionnisme, Paris, Gallimard, 2006

Loos, Adolf, Paroles dans le vide – Malgré tout, Paris, Champ Libre, 1979

Lukacs, Georg, Histoire et conscience de classe, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1960

Lugon, Olivier, La Photographie en Allemagne. Anthologie de textes (1919-1939), Nîmes, Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, 1997

Makela, Maria, The Munich Secession. Art and Artists in Turn of the Century Munich, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990

Mazellier-Grünbeck, Catherine, Le Théâtre expressionniste et le sacré : Georg Kaiser, Ernst Toller, Ernst Barlach, Berne, P. Lang, 1994

Mellor, David (éd.), Germany : The New Photography 1927-1933, London, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978

Michalski, Sergiusz, Nouvelle objectivité, Cologne, Taschen, 1994

Michaud, Éric, Un Art de l’éternité : l’image et le temps du national-socialisme, Paris, Gallimard, 1996

Middleton, Christopher, Bolshevism in Art and Other Expository Writings, Manchester, Carcanet New Press, 1978

Midgley, David R., Writing Weimar : Critical Realism in German Literature 1918-1933, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000

Miesel, Victor H., Voices of German Expressionism, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, 1970

Miller-Lane, Barbara, Architecture and Politics in Germany 1918-1945, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1968

Mitzman, Arthur, « Anarchism, Expressionism and Psychoanalysis », New German Critique, no10, Winter 1977

Moholy-Nagy, Lazlo, Peinture Photographie Film et autres écrits sur la photographie, Nîmes, Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, 1993

Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl, Moholy-Nagy : Experiment in Totality, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1969

Möller, Horst, La République de Weimar, Paris, Tallandier, 2005

Mosse, George L., De la Grande Guerre au totalitarisme. La Brutalisation des sociétés européennes, Paris, Hachette, 2003

Musil, Robert, L’Homme sans qualités, Paris, Seuil, 2004, 2 tomes

Musil, Robert, Journaux, Paris, Seuil, 1981, 2 volumes

Myers, Bernard Samuel, Expressionism : A Generation in Revolt, New York, Praeger, 1957

Naubert-Riser, Constance, La Création chez Paul Klee, Paris, Klincksieck, 1978

Palmier, Jean-Michel, L’Expressionnisme comme révolte, Paris, Payot, 1978

Palmier, Jean-Michel, L’Expressionnisme et les arts, Paris, Payot, 1979-1980, 2 volumes

Palmier, Jean-Michel & Van Deren Coke, 1919-1939 : Avant-garde photographique en Allemagne, Paris, Sers, 1982

Palmier, Jean-Michel, Weimar en exil, Paris, Payot, 1990

Palmier, Jean-Michel, L’Art dégénéré, Paris, Bertoin, 1992

Pan, David, Primitive Renaissance : Rethinking German Expressionism, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 2001

Paret, Peter, The Berlin Secession : Modernism and its Enemies in Imperial Germany, Cambridge, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980

Pehnt, Wolfgang, Expressionist Architecture, London, Thames & Hudson, 1973

Pierce, James S., Paul Klee and Primitive Art, New York, Garland, 1976

Piscator, Erwin, Le Théâtre politique, Paris, L’Arche, 1972

Plassard, Didier, L’Acteur en effigie : figures de l’homme artificiel dans le théâtre des avant-gardes historiques, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1992

Poggioli, Renato, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (1962), Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1968

Poirier, Alain, L’Expressionnisme et la musique, Paris, Fayard, 1995

Ragon, Michel, L’Expressionnisme, Lausanne, Éditions Rencontre, 1966

Raabe, Paul (éd.), The Era of German Expressionism, London, Calder & Boyer, 1974

Reisenfeld, R., « Cultural Nationalism, Brücke and the German Woodcut : The Formation of a Collective Identity », Art History, 20/2, 1997

Richard, Lionel, D’une Apocalypse à l’autre ; Sur l’Allemagne et ses productions intellectuelles de Guillaume II aux années vingt, Paris, U. G. E., 1976

Richard, Lionel (éd.), L’Expressionnisme allemand, Obliques, numéro 6-7, 1976

Richard, Lionel, Le Nazisme et la culture, Paris, Maspero, 1978

Richard, Lionel, Encyclopédie du Bauhaus, Paris, Somogy, 1985

Richard, Lionel (éd.), Encyclopédie de l’expressionnisme, Paris, Somogy, 1978

Richard, Lionel, Cabaret Cabarets, Paris, Plon, 1991

Richard, Lionel, Berlin 1919-1933. Gigantisme, crise sociale et avant-garde : l’incarnation extrême de la modernité, Paris, Autrement, 1999

Richard, Lionel (éd.), Expressionnistes allemands. Panorama bilingue d’une génération, Bruxelles, Éditions Complexe, 2001

Richter, Hans, Dada Art & Anti-art, Bruxelles, Éditions de la Connaissance, 1966

Ringbom, Sixten, « Art in ’’The Epoch of the Geat Spiritual’’ : Occult Elements in the Early Theory of Abstract Painting », Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 29, 1966

Ringbom, Sixten, The Sounding Cosmos : A Study in the Spiritualism of Kandinsky and the Genesis of Abstract Painting, Abo, Acta Academia Aboensis, 1970

Ringbom, Sixten, « Paul Klee and the Inner Truth to Nature », Arts Magazine, 52/1, September 1977

Roethel, H. K., The Blue Rider, New York, Praeger, 1971

Rogoff, Irit (éd.), The Divided Heritage. Themes and Problems in German Modernism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991

Rousso, Henri (éd.), Stalinisme et nazisme. Histoires et mémoires comparées, Bruxelles, Complexe, 1999

Rumold, R. & O. K. Werkmeister (éds.), The Ideological Crisis of Expressionism, Columbia, Camden House, 1990

Russell, Charles, Poets, Prophets and Revolutionnaries : The Literary Avant-Garde From Rimbaud to Postmodernism, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1985

Sabarsky, Serge (éd.), La Peinture expressionniste allemande, Paris, Herscher, 1990

Samuel, Richard et Thomas R. Hinton, Expressionism in German Life, Literature and the Theatre, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1939

Scheuneman, Dietricht (éd.), Expressionist Film. New Perspectives, Rochester, Camden House, 2003

Schmalenbach, Fritz, « The Term ‘’Neue Sachlichkeit’’ », Art Bulletin, no22, 1940

Schneede, Uew M., George Grosz. The Artist in His Society, Woodbury, Barron’s, 1985

Schoenberg, Arnold, Le Style et l’idée, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1977

Schoenberg, Arnold, Correspondance 1910-1951, Paris, Lattès, 1983

Schoenberg, Arnold, « Entretien sur la peinture », Musique en jeu, numéro16, novembre 1974

Schoenberg, Arnold, « La Main heureuse », Contrechamps, numéro 2, 1984

Schoenberg, Arnold et Wassily Kandinsky, « Correspondance et écrits », Contrechamps, numéro 2, 1984

Schorske, Carl E., Vienne, fin de siècle, Paris, Seuil, 1983

Schvey, Henry I., Oskar Kokoschka. The Painter as Playwright, Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1982

Schwitters, Kurt, Merz. Écrits choisis, Paris, Gérard Lebovici, 1990

Scotti, Roland, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner : The Photographic Work, Göttingen, Steidl/Kirchner Museum Davos, 2006

Sers, Philippe, Totalitarisme et avant-garde, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2001

Seuphor, Michel, Le Style et le cri, Paris, Seuil, 1965

Seuphor, Michel, L’Art abstrait, Paris, Maeght, 1971

Sharp, Dennis, Modern Architecture and Expressionism, New York, George Braziller, 1966

Sharp, Francis Michael, « Expressionism and Psychoanalysis », Pacific Coast Phililogy, vol. 13, October 1978

Sheppard, Richard « Kandinsky’s Oeuvre 1900-1914 : The Avant-Garde as Rear-Guard », Word & Image, January-March, 1990

Sofsky, Wolfgang, L’Ère de l’épouvante. Folie meurtrière, terreur, guerre, Paris, Gallimard, 2002

Stern, J. P., The Politics of Cultural Despair : A Study in the Rise of Germanic Ideology, New York, Doubleday, 1965

Taylor, Brandon & Wilfried van der Will (éds.), The Nazification of Art. Art, Design, Architecture and Film in the Third Reich, Winchester, Winchester Press, 1990

Taylor, Seth, Left-Wing Nietzscheans : The Politics of German Expressionism, 1910-1920, New York, Walter de Gruyter, 1990

Teitelbaum, Matthew (éd.), Montage and Modern Life 1919-1942, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1992

Toniutti, Emmanuel, Paul Tillich et l’art expressionniste, Québec, P. U. L., 2005

Tossato, Guy, Allemagne années 20 : la Nouvelle Objectivité, Paris, Réunion des Musées nationaux, 2003

Tower, Beeke Sell, Klee and Kandinsky in Munich and at the Bauhaus, Ann Arbor, UMI Research Press, 1981

Trakl, Georg, Œuvres complètes, Paris, Gallimard, 1972

Tschichold, Jan, Livre et Typographie, Paris, Allia, 1994

Tudor, Andrew, « Elective Affinities : the Myths of German Expressionism », Screen, 12/12, 1971

Tudor, Andrew, « The Famous Case of German Expressionism », Image and Influence Studies in the Sociology of Film, London, Allen & Unwin, 1974

Tzara, Tristan, Œuvres complètes, Paris, Flammarion, 1975-1982

Vallier, Dora, L’Art abstrait, Paris, Hachette, 1980

Vallier, Dora, La Rencontre Kandinsky-Schoenberg, Caen, L’Échoppe, 1987

Varnedoe, Kirk, Vienne 1900, Cologne, Taschen, 1989

Vergo, Peter (éd.), Towards a New Art ; Essays on the Background to Abstract Art, Londres, The Tate Gallery Publication Department, 1980

Vienne, début d’un siècle, Critique, numéro 339-340, août-septembre 1975

Vogt, Paul, « Introduction », Expressionism : A German Intuition 1905-1920, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1980

Vuillermoz, Émile, « Réalisme et expressionnisme », Les Cahiers du mois, numéro 16-17, 1925

Waldman, Diane, Collage, Assemblage and the Found Object, New York, Abrams, 1992

Washton-Long, Rose-Carol, « Kandinsky’s Vision of Utopia as a Garden of Love », Art Journal, XLIII/1, 1983

Washton-Long, Rose-Carol (éd.), German Expressionism : Documents from the End of Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National-Socialism, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995

Weininger, Otto, Sexe et caractère, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1975

Weinstein, Joan, The End of Expressionism : Art and the November Revolution in Germany 1918-1919, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1990

Weisgerber, Jean (éd.), Les Avant-gardes au vingtième siècle, Budapest, Akademiai Kindo, 1984

Weiss, Peg, Kandinky and Old Russia : The Artist as Ethnographer and Shaman, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995

Weisstein, Ulrich, « Expressionism in Literature », in Philip P. Wiener (éd.), Dictionary of the History of Ideas, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1973

Weisstein, Ulrich (éd.), Expressionism as an International Literary Phenomenon, Paris/Budapest, Librairie Marcel Didier/Akadémiai Kiado, 1973

Werenskiold, Marit, The Concept of Expressionism : Origin and Metamorphoses, New York, Columbia University Press, 1984

Werkmeister, O. K., « The Issue of Childhood in the Art of Paul Klee », Arts Magazine, 52/1, September 1977

Werkner, Patrick, Egon Schiele : Art, Sexuality and Viennese Modernism, Palo Alto, Society for the Promotion of Science & Scholarship, 1994

Willett, John, Expressionism, London, McGraw-Hill, 1971

Willett, John, The New Sobriety : Art and Politics in the Weimar Period 1917-1933, London, Thames & Hudson, 1978

Willett, John, Les Années Weimar : une culture décapitée, Paris, Hazan, 1984

Willett, John, L’Esprit de Weimar. Avant-gardes et politique 1917-1933, Paris, Seuil, 1991

Wood, Paul et alli, Art en Théorie : 1900-1990 : une anthologie, Paris, Hazan, 1997

Wörringer, Wilhelm, Abstraction et Einfühlung ; Contribution à la psychologie du style, Paris, Klincksieck, 1982

Wurgaft, Lewis D., The Activists : Kurt Hiller and the Politics of Action in the German Left, 1914-1933, Philadelphie, American Philosophical Society, 1977