Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER,

Baigneurs, 1909, 75,5 X 101, Wuppertal, Von Der Heydt Museum

Like Matisse and Picasso, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel were obsessed with the female nude, as a symbol of their own intense sexuality as well as a seductive return to primitive nature. But the Southern landscapes of Matisse and Picasso are a long way from the Northern woods surrounding Kirchner’s Bathers at Moritzburg (1909) and those in Heckel’s Forest Pond (1910).

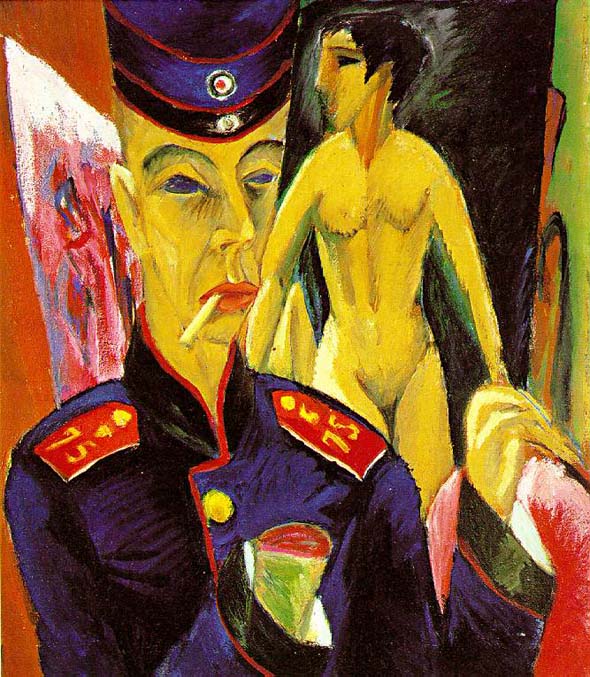

In the cold North, one could only strip naked and bathe during the summer ; otherwise one is restricted to the urban studio. The imagery of Kirchner and Heckel oscillates between indoor and outdoor scenes, sometimes with an attempt to make the indoors seem like the healthier outdoors, as in Kirchner’s Fränzi with Bow and Arrow (1909-11), Girl with Cat, Fränzi (1910) and Nude Behind a Curtain; Fränzi (1910-26), where exotic nature motifs, derived from the warm tropics, form the background. The female nude fits right in, as the forest green and sky blue contours of her flattened body indicate. In Self-Portrait with Model (ca. 1910), Kirchner is implicitly naked -- the natural man -- under his robe, which is as colorful and fresh as the landscapes in his outdoor paintings. Thus the studio is an exotic and erotic world apart -- a kind of "second nature," as it were.

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER,

Baigneurs à Moritzburg, 1909

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER,

Autoportrait avec modèle, 1910 (-1926), 150,4 X 100, Hambourg, Kunsthalle

For Kirchner and Heckel, woman’s naked body was always primal, rather than simply a studio prop, as it often seemed to be for Matisse and Picasso, however much they used it for their own expressive purpose. Woman’s naked presence was healing, as well as emblematic of sexual freedom and pleasure.

To strip naked was a socially revolutionary act as well as a revolutionary return to origins. For the German Expressionists, the former entailed the latter : one didn’t rebel against existing society to make a better society, but to escape society altogether by returning to nature. One felt more alive and healthy in it than one ever could in society. Kirchner’s Striding into the Sea (1912) shows the existentially ideal situation : a man and woman, unashamed of their nakedness, fearlessly walking into the ocean together. Forgetting that they ever wore clothes, they have become natural creatures in a natural environment. They are lovers, rather than at odds, at peace with one another rather than antagonists in the battle between the sexes. They are emotional equals, sharing the redemptive freshness of the sea, renewing themselves by entering the element in which life originated.

Utopia is still possible, the picture suggests : one can escape society and recover one’s authenticity in nature -- escape the modern world and recover one’s sense of inhabiting the body given to one by nature, which is fundamental to one’s sense of being.

Kirchner’s new Adam and Eve are a long way from the properly dressed men and women -- their bodies are censored by their clothes -- he observed on a Dresden Street (1908), a Berlin Street (1913) and Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse (1914), just as his lush Landscape in Spring (1909) is a long way from the desolate man-made space depicted in The Red Tower in Halle (1915). The women in the two Berlin paintings are prostitutes, emotionally stunted women renting their bodies to whomever can pay the price. They are urban necessities -- socially sanctioned outlets for sexually uptight, lonely men.

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER,

Friedrichstrasse, 1914

In sharp contrast, the emotionally healthy nature nudes give themselves freely to the lover of their choice, without worrying about social conventions and constraints. The men they love are as comfortable with their own bodies as the women are with their naked bodies. For both, love-making is a spontaneous, natural, guiltless act rather than a compulsive rebellion against social repression, which as such is likely to be fraught with emotional problems. We see such natural lovers in a series of drawings that Kirchner made in 1909. They are daring drawings, not so much because they show naked people making love -- the quickness of the lines suggests the spontaneity with which they do so -- but because they show them smiling happily as they do so.

Kirchner and Heckel were the leading figures in "Die Brücke" ("The Bridge"), an organization of artists that originated in Dresden in 1905, and disbanded in 1913. (In 1911 Kirchner, Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, the other major figure, moved to Berlin.) They are the seminal German Expressionists, along with "Der Blaue Reiter" ("The Blue Rider").

This latter was a more informal group of artists, loosely associated with Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc around 1912, the year they produced their so-called Almanac (it appeared only once). Their purpose was different : Brücke imagery oscillates between urban society and natural paradise -- the studio is an intermediate zone, a kind of limbo in which both can meet -- while Blaue Reiter imagery is mystical. Both groups were emotional revolutionaries -- emotional freedom mattered to them above all -- but the Blaue Reiter artists were more esthetically revolutionary than the Brücke artists. The former carried Expressionism to an abstract extreme -- they were in pursuit of complete esthetic freedom, which meant freedom from representation -- that the latter never approached, however free their handling. For both, esthetic freedom was a symbol of emotional freedom -- the therapeutic freedom to express one’s emotions, leading one to discover that one had emotions one didn’t know one had. But the Blaue Reiter artists were freer than the Brücke artists because they also wanted spiritual freedom -- the freedom that came with having a higher consciousness, giving one a sense of being a completely integrated self. They are less concerned with the difference between the unhealthy urban environment and the health-giving landscape than they are with the transcendence of both.

Because of this, Blaue Reiter Expressionism is different in kind from Brücke Expressionism, both in its visual dynamics and idealism. This is why it will be considered in the next chapter, along with the work of other abstract artists -- the first to emerge in the twentieth century -- with a similar interest in conveying transcendental experience by abstract means.

However much conflict there is in Blaue Reiter art, it is about resolving conflict, rather than displaying it, as Brücke art, taken as a whole, does. There may be moments of conflict-resolution in nature, but then nature is always at odds with society in Brücke art. Sexual intimacy is a short-lived triumph over society. In Blaue Reiter art, on the other hand, there are neither life-redeeming natural nudes nor life-threatened prostitutes, which clearly sets it apart.

Presumably the absence of the female factor shows its higher purpose. It is an art of sublimation -- it strives to be sublime, and to represent the sublime -- rather than of sexual anxiety. Indeed, it assumes that one can escape anxiety – Cézanne’s anxiety, countered by Matisse’s hedonism and escalating into Picasso’s destructiveness (the fork in the road of early twentieth century art) -- by becoming abstract, that is, detached from external reality (if not entirely removed from subjective reality).

As Kirchner’s Nude in a Blooming Meadow (1909) makes clear, the Brücke artists were influenced by Fauvism, and as Still Life with Mask and the emphatic features of the mask-like face of the Nude on a Blue Ground (both 1911) show, they were also influenced by African masks, like Matisse and Picasso, as well as Oceanic art. (Indeed, Gauguin was more important to them than Cézanne.) But these masks meant different things to the French and German artists. For the latter, they were the instruments of an investigation into the origin of creativity, not only a dramatic expressive device, socially and esthetically rebellious. The masks symbolized the law of the jungle, and the law of the jungle was a breath of creative life, freedom and originality for the Brücke Expressionists, not only an esthetic opportunity. In Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the mask is a startling representational novelty, substituting for the natural appearance of the all-too-familiar human face, and thus socially disturbing. But in Kirchner the mask is the direct expression of inner life, and as such inherently creative rather than a superimposed idea.

Wilhelm Uhde’s advocacy of naive painting and Paul Klee’s fascination with children’s art -- already in 1912 he praised it -- were part of the same attempt to understand the nature of creativity. To be creative meant to return to primordial nature -- the implicit goal was to be as creative as nature. More particularly, it meant the recovery of primordial human nature from its social encrustations, which is what naive painting, children’s art and African masks -- and later, in the 1920s, psychotic art -- was thought to accomplish. Primitivism is peculiarly archaeological, in that it is an attempt to dig up what has been buried alive by society ; only the spiritually innocent can succeed in doing so. Kirchner’s own primitive sculptures, like Male Nude -- Adam and Female Nude -- Eve (both 1923), are magnificent examples of his wood carving, more convincing in their primitivism than Picasso’s earlier primitivist sculptures (as is Heckel’s Crouching Woman (1914) -- seem to have been excavated from the depths of the earth, as though from a forgotten layer of archaic time. They seem to have been made by someone who never knew classical sculpture -- certainly not at its most refined. Indeed, someone who was completely untrained in the making of fine art -- some anonymous person from a primitive civilization, if it can be called that.

The works of untrained artists were presumably natural, innocent expressions -- spontaneous, original creations, free of unnecessary civilized refinements. The Brücke artists struggled to achieve the untrained, primitive, naively expressive look of innocent emotionality -- Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh were also their models in this -- as their nudes and landscapes show. They wanted no Cubist irony -- no Cubist spatial sophistication : Cubist ambiguity was artificial and manufactured, and as such pseudo-expressive, rather than natural and spontaneous, and thus authentically expressive and experiential. From a German Expressionist point of view, Cubism (Kirchner repudiated it as inhuman, "far from the real soil of art") is an intellectual fabrication rather than an emotional response to nature that captures its originality, thereby making itself original, that is, an expression of primordial being. Cubism has a supercilious attitude to nature, and as such is blind to its elemental originality -- out of touch with what is most alive, visceral and existentially significant in it.

The critic Clement Greenberg argued that Cubism was the esthetic high road of twentieth century art, and for this reason more authentically avant-garde than Expressionism. For Cubism pointed the way to pure, autonomous art -- art that is about nothing other than itself, in an endless process of self-criticism, purging itself of everything that is beside the point of its material medium, especially what Greenberg called "human interest" (painting is not story-telling or picture-making, but rather about surface, space and color as such). Nonetheless, Expressionism remains the most influential twentieth century art because of its emphasis on self-expression in a society in which the self is at risk, as the Brücke artists recognized.

Expressionism is also far from indifferent to the medium, as Brücke woodcuts, and the general expressionist emphasis on texture and facture, indicate. In fact, Expressionism involves a constant search for new material and imagistic means to express the self, for it realizes that none are ever quite adequate to its depth and subtlety. The self quickly outgrows its medium, requiring a fresh investment of it in a new medium of expression. To an Expressionist, every medium seems limited -- the German Expressionists worked in all of them -- because self-expression is limitless, and more complex than any material.

(The woodcuts are the most dramatically primitivist and expressive work produced by the Brücke, especially because of the extremes of black and white that define their space. They have an air of precarious spontaneity that is quintessentially Brücke, all the more so because it recapitulates the awkwardness of medieval German woodcuts. They also liked working in wood -- their wood sculptures are another example -- because it was a natural material. In general, the Brücke artists were influenced by German medieval art, which they experienced as primitive, if not in the same manner as African and Oceanic art. But both had nothing to do with classical art, particularly in its Renaissance reincarnation.)

Cubism has become obsolete, but Expressionism has survived, constantly re-inventing itself, as shown by the American Abstract Expressionism of the 1940s and 1950s, and the Berlin New Fauves ("Neue Wilden") and more broadly the New German Expressionism that emerged in the 1980s. This suggests that the self remains under siege in the modern world -- that emotional freedom, or what the historian Meyer Shapiro called "inner freedom," remains rare -- and that art must serve it with every means at its disposal. This gives art a sense of inner purpose -- what Kandinsky referred to as "inner necessity" -- which it loses once it has become totally pure. Purity dead-ends in sterility, as is clear from the Post-Painterly Abstraction -- really Post-Expressionistic Abstraction -- that Greenberg advocated in the 1960s, as the next "real" avant-garde step.

The Expressionist nude in the Expressionist landscape conveys the seamless merger of human nature and the nature in which it was originally at home -- the nature that is the most authentic expression of being. The difference between the Brücke representation of nature and of urban reality parallels the distinction between the creative state of being that comes from being natural and the uncreative result of an unnatural way of life. The return to nature in Brücke imagery is a return to creative originality, which the individual loses in the crowded modern city. What was necessary was a re-naturing of the denatured individual, who could then passionately express his or her natural creativity. In short, the therapeutic goal of Brücke Expressionism was the recovery of innate creativity, more particularly, the spontaneously creative, emotionally resonant artistic expression natural to human nature.

Erich HECKEL,

Convalescence, 1913, Fogg Art Museum

The issue of a creative cure for emotional ailments haunts Brücke art. Heckel’s triptych Convalescence (1913) is the consummate example. In the center is an urbane, sickly woman. Her angular chin and elbows suggest the unnatural, indoor way of life that made her sick, and her agitated fingers convey her anxiety. She is clearly not at ease in her person, as her pained, tense expression confirms. Her suffering seems more mental than physical. Deliberately holding herself upright, she nonetheless is unable to lift herself off her bed, despite the fact that she has no physical disability. The weakness of her body is an expression of her mental suffering. The right panel shows giant sunflowers, turned toward her with their life-giving luminosity and radiance -- their glorious warmth. Compared to them, she seems small and irrelevant. The natural, expansive curves of the sunflowers form a startling contrast with the unnatural angles of the woman’s cramped body. The left panel shows another plant and a peasant girl -- a kind of primitive, who seems carved out of wood. She is a sturdy creature -- the antithesis of the emotional invalid she is attending. The flourishing plants have all the joie de vivre that the convalescent woman lacks. They have the healing power of nature in full bloom. Their natural presence should help her recover her health -- the good mental health that comes from being natural.

Heckel’s dramatic juxtaposition of the living, growing, healthy, extroverted plants and the sickly, city-bred, sophisticated, introverted woman -- the tension between them is unresolved, for it is not clear that she is receptive to their vitality, not clear that she has the will to recover -- epitomizes Brücke art. Heckel’s convalescent could be a patient in the sanatorium that Thomas Mann described in his novel The Magic Mountain (1924). Like many of the patients there, she may be a chronic case. She has come for the cure, but she may be incurable -- a permanent invalid.

Ernst Ludwig KIRCHNER,

Autoportrait en soldat, 1915

The contest between sickness and health -- the "sickness unto death," as Soren Kierkegaard called depression, and nature, which represents health and happiness -- has ended in a tie in Heckel’s masterpiece. Sometimes Brücke pictures are entirely about excruciating suffering – Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as Soldier and Artillery Men (both 1915) are famous examples (in the former, Kirchner has lost his painting arm, suggesting his feeling of castration, while the latter are herded together in a claustrophobic space and victimized by an authority figure) -- and sometimes they are exclusively about health, especially when they depict nature. Indeed, the Brücke artists sought health in untouched nature, the more untouched -- uncivilized -- the better. Schmidt-Rottluff traveled to the remotest reaches of Norway to find raw terrain ; Emile Nolde, who briefly joined the Brücke in 1905, found inspiration "in the brisk air of the North Sea," as Kirchner said ; and Heckel and Kirchner found it in the area around the Moritzburg lakes, where they were able to paint the female nude outdoors, as though she was a part of the landscape, her body an expression of unadulterated nature. In general, for the Brücke artists, the female body registered every nuance of nature, and the mood in which the artist expressed his nature.

Brücke landscapes are sometimes allegories of sickness and health, like Heckel’s Convalescence. Heckel’s Landscape in Thunderstorm (1913), with its burst of light from dark clouds, suggests that radiant health might come from great suffering -- from a depression that brings one to the door of psychic death. Mental suffering and physical sickness were paradoxical for the Brücke painters: they were tests of strength, will power and endurance. If one had the courage to survive them, they showed themselves to be rites of passage to a more wholesome, vigorous, natural state of being than is ever possible in society.

Sometimes sickness is explicitly mental, and incurable, as Heckel’s The Madman (1914) makes clear. The Brücke artists in general were interested in extreme mental states, just as they used extreme colors. But the disturbed person is often a young woman, as Heckel’s Sick Girl (1912) and Suffering Girl (1914) indicate, although, as Kirchner’s Sick Woman ; Woman with Hat (1913) as well as Heckel’s Convalescence show, she can be older. It is to their credit that the Brücke artists do not present woman simply as a sex object -- nothing but a desirable body -- but give women an inner life, and with that autonomy. They in fact see women as all too human in a way that Matisse and Picasso rarely do. Even earlier, in woodcuts made between 1905-10, woman is presented, by both Heckel and Kirchner, as a somewhat troubled, introverted being, except when she is extrovertedly at play in nature. The problem was to feel more alive than dead in a society that made one feel more dead than alive. Woman was the symbol of life, but she too had become tainted by death, almost losing her will to live, becoming listless and depressed -- except when she represented life in nature. For Heckel and Kirchner, woman became the battleground on which the struggle between sickness and health -- depression and vitality -- was fought.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in their fascination with the immature, unwholesome body of the adolescent Fränzi, whom both portrayed. Breastless and thin, she hardly seems a woman, even as her erotic allure -- she wears bright red lipstick -- suggests that she is a grown one. She is an unsavory mix of femme fatale and innocent child, neither exactly true to who she is. She is in fact an indifferent girl who has no identity, and as such is the perfect instrument for the artists’ fantasies. She is a blank screen on which they can project their own confused identities. Kirchner’s Girl with Cat, Fränzi and Heckel’s Fränzi with Doll (1910) are strangely sick pictures, all the more so because they turn her into an exotic native. She looks as though she’s been carved of wood, and as such theatrically contrived and crudely natural at once -- a fake primitive. In both works, Fränzi seems depressed by the role she plays, even as her bright coloration suggests her vitality. She remains unmoved by all the attention she receives, inert despite the animated color that covers her like tattoos. They eroticize her body into a fantastic mirage, but the blink of an eye shows it to be a farcical illusion. They try to make her into pure, eager, hot-blooded instinct -- which is what they felt themselves to be, for all their emotional troubles -- but underneath she remains as cold as society.

Fränzi epitomizes their ambivalence about woman -- and themselves.

Uncertain as to whether she is a naive girl or a knowing woman -- uncertain about her body and state of mind -- she represents their own uncertainty about their psychosomatic state. The manic color of their paintings, and the often depressed figures they paint, show their effort to transform sickness into health. Or else the possibility of health proposed through the color is a defense against the melancholy mood of the figures, which lifts only when they leave society for nature. Heckel’s Two Friends (1912) are a long way from the naked couple Striding into the Sea. They have to escape from society, or they will be scorned and mocked by it, like Kirchner’s Couple before the People (1924). Kirchner’s couple are free spirits, as their nakedness shows, and like Christ in many medieval pictures – Kirchner’s painting is consciously composed like one -- they are spat upon by the crowd.

"Art as the only superior counterforce to all will to denial of life," Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in one of the fragments that came to be collected after his death in The Will To Power (1901), and the art of the Brücke seems concentrated in their luminous color, which is full of life, and thus triumphs over the disease of denying life that so many of their figures seem to suffer from. Nietzsche was an important influence on the Brücke artists and Expressionism in general, particularly because he believed that the artist was -- or should be -- that most healthy and heroic of human beings, the Übermensch. Indeed, Heckel made a 1905 woodcut portrait of him looking like one -- it is worth comparing to the more demented looking 1912 portrait by Otto Dix -- suggesting just how great an inspiration he was to the Brücke artists. (Nietzsche thought of himself as an artist, although he was far from healthy physically and mentally, and had little insight into himself, however grand a conception of himself he had.) For Nietzsche "art and nothing but art... is the great means of making life possible, the great seduction to life, the great stimulant of life.... Art as the redemption of the sufferer -- as the way to states in which suffering is willed, transfigured, deified, where suffering is a great delight."

It was not exactly that for the Brücke artists, nor do they seem to have willed their suffering, but suffered involuntarily, like other victims of life. Moreover, while they regarded primitive life in nature and primitive art as healthy, they sometimes found that even primitive people suffered, as Kirchner’s crude Old Peasant (1919-20), Paula Modersohn-Becker’s pious Old Peasant Woman (ca. 1905-7) and grim Old Poorhouse Woman with Glass Bottle and Poppy (1906) indicate. The Expressionists never lived up to Nietzsche’s extravagant ideal of the artist. And art didn’t always work to redeem life for them, especially when life became exceptionally difficult, as Kirchner’s post-war mental breakdown and later suicide (1938), in the wake of being labeled a degenerate artist by the Hitler regime, suggests. Nor is it clear that they had Nietzsche’s fanatical belief in the life-giving power of art -- however much they wanted to be true believers -- as the persistent morbid undertone to their art indicates.

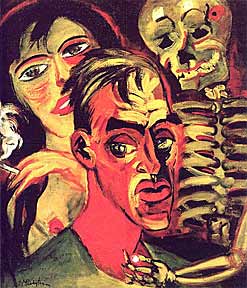

Max PECHSTEIN,

Autoportrait avec la Mort, 1920

Max Pechstein understood that suffering was also sometimes present in pleasure, as his 1920 Self-Portrait with Death and a lurid nude suggests. (It is a work in the Germanic Triumph of Death tradition, relating particularly to Hans Baldung-Grien’s pictures of beautiful women and Death.) He has clearly come a long way from Evening in the Dunes (1911), with its voluptuous female nudes, made all the more seductive by the red of the setting sun. Unlike Pechstein, Modersohn-Becker was not a member of the Brücke, but she understood that suffering could last a lifetime -- right to death -- and she knew that flowers were hardly the consolation that Heckel seemed to think they were in Convalescence. She also knew that art was better at representing suffering than redeeming it -- better at representing the denial of life than its affirmation, as Nolde’s famous gloomy, somewhat demented Prophet (1912) suggests. Even Nolde’s primitively painted images of the life of a rather primitive Christ (1909-12) were morbid, for all their brilliant, in-your-face color. It is worth noting that they were begun after a serious illness, and seem designed to recuperate his emotional losses -- to lift him out of depression -- as their bizarre, somewhat disturbed, compulsive (certainly headlong) expression of "spirituality, religion and inwardness" (his words) suggests. They, in fact, seem to have more to do with madness than spirituality. Certainly, their grotesquely distorted figures and harsh, manic texture -- their general air of vehemence and violence -- have little to do with the usual idea of spiritual aspiration, although there is perhaps a relationship to the kind of spirituality visible in Louis Corinth’s Dancing Dervish (1904), an influential proto-Expressionist painting.

Paula MODERSOHN-BECKER,

Selbstbildnis nach halblinks mit Hand am Kinn, 1906, 29 X 19,5, Hanovre, Leihgabe in der Niedersächsischen Landesgalerie

Modersohn-Becker’s Self-Portrait with Camellia (1907) and Ludwig Meidner’s My Night Visage (1913) are the extremes of Expressionist self-portraiture. To my mind’s eye, the portrait of the madman wins out over the portrait of the gently smiling woman. Meidner’s portrait seems truer to his inner life than Modersohn-Becker’s seems to her inner life. His weird expression and staring eyes -- his general confrontational demeanor -- seem more psychologically authentic than her tranquil smile, which seems posed -- all too deliberate -- however genuine the feeling of well-being it conveys may be. But even Modersohn-Becker has a dark side, as the black inner frame and her mask-life face -- it has a certain resemblance to that of Picasso’s Gertrude Stein -- suggests. Her fixed smile seems to hide something more ominous in her personality -- something evident in her imposing, primitive figure.

The German Expressionists were more attuned to dementia than happiness -- more afraid of going mad than determined to enjoy life and nature. The fear of madness poisoned their feeling for life and nature, which was an escapist antidote for it that did not always work. Apart from the fact that Meidner’s turbulent handling and dark background, broken by his illuminated figure and the lurid contrast of red and green (the blood red neck suggests that he might just be crazy enough to slash his neck, and the flash of whiteness on his forehead suggests the explosive electricity in his brain) make for a more dramatic, intense picture than Modersohn-Becker’s use of subdued tones, muted contrasts and a generally pious atmosphere, Modersohn-Becker’s picture lacks the hallucinatory quality and visionary power of Meidner’s. In 1912, in an essay "On the Nature of Visions," the Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka declared that art involves reaching "a level of consciousness at which we experience visions within ourselves."These visions impart "a power to the mind," and "can be evoked but never defined." Modersohn-Becker’s self-portrait is all too defined, and lacks the disruptive -- and eruptive -- dream-like quality that Kokoschka regards as essential to a vision. Modersohn-Becker’s portrait does not "RELEASE CONTROL" -- Kokoschka capitalizes the words that epitomize the Germanic idea of expression -- but rather suggests an all too controlled person, rather than one whose "self and personal existence" have been "fused into a larger experience" -- the experience of the unconscious. It is an experience of what the Neo-Expressionist Georg Baselitz calls "pandemonium," the sign of madness.

In short, Modersohn-Becker’s self-portrait does not show the release of conscious control -- the madness in both handling and image -- that Meidner’s does. Her face is not beside itself with unconsciousness. It has not surrendered itself to unconscious expression, to forces beyond her control: Modersohn-Becker’s face is not distorted by the urgent, uncontainable unconscious forces that have wrecked Meidner’s face, suggesting that he has almost lost his conscious sense of himself. Her self-portrait thus lacks visionary intensity : she keeps a straight face. She has a secure sense of herself. The difference between inner and outer selves -- emotional reality and outer appearance -- has not been blurred, as it has in Meidner’s self-portrait. We understand and empathize with her, but we do not understand and empathize with Meidner. It is too dangerous to do so -- to enter into the spirit of his picture is to become mad ourselves. The conflict between conscious control and loss of control because of the explosive unconscious is what makes Meidner’s visage so terrifying. Thus Modersohn-Becker’s self-portrait does not arise from the depths of her unconscious as his does.

Hers is not an unconscious self-expression, that is, an expression of her unconscious sense of herself. Her picture is not marked by the dynamics and drama of the unconscious the way genuine (self-) expression is for the German Expressionists. Instead, it reveals her self-consciousness, self-possession, self-control, however deeply moved she seems to be. But happiness is not as deep as madness, as Meidner’s genuinely expressionist self-portrait indicates.

Donald KUSPIT, « New Forms For Old Feelings : The First Decade » (chapitre I, partie 4 de A Critical History of the 20th-Century Art)

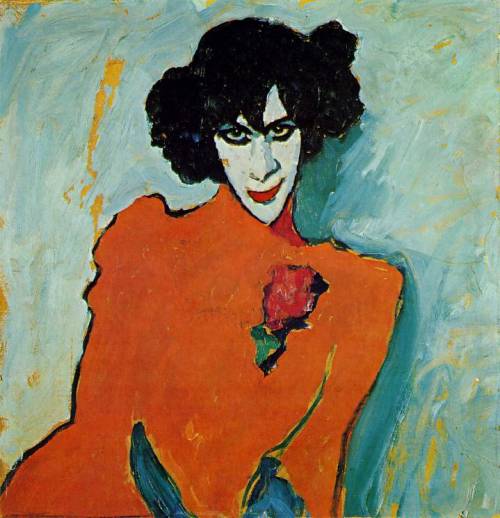

Alexei von JAWLENSKY, Portrait du danseur Alexander Sacharoff, 1909, 70 X 67, Munich, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus

Alexei von JAWLENSKY, Portrait du danseur Alexander Sacharoff, 1909, 70 X 67, Munich, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus  Gabriele MÜNTER (1877-1962)

Gabriele MÜNTER (1877-1962) Paula MODERSOHN-BECKER, Selbstbildnis nach halblinks mit Hand am Kinn, 1906, 29 X 19,5, Hanovre, Leihgabe in der Niedersächsischen Landesgalerie

Paula MODERSOHN-BECKER, Selbstbildnis nach halblinks mit Hand am Kinn, 1906, 29 X 19,5, Hanovre, Leihgabe in der Niedersächsischen Landesgalerie