Gabriele MÜNTER (1877-1962)

Gabriele Munter's lively experiments in painting helped establish the Expressionist style--sometimes despite her conflicted "mentor" relationship, with Wassily Kandinsky--at a time when women had virtually no access to artistic training.

In the often anxious realm of German Expressionism, a world of virility, domination and apocalyptic visions, Gabriele Munter stands alone.[1] One of a very few, remarkable women associated with the movement, she helped establish a style but made no theoretical or metaphysical claims for it, going unpretentiously about her business as an artist, painting still lifes, portraits and landscapes with bold shapes and glowing colors. Her vibrant experiments are currently the focus of a retrospective curated by Expressionist scholar Reinhold Heller, whose substantial research has produced a catalogue that is now the definitive source for Munter studies in English.[2] With loans from German, Austrian and American collections, the exhibition includes 82 paintings, prints and drawings from Munter's early maturity--the Expressionist years coinciding with her artistic and romantic partnership with Wassily Kandinsky. Munter lived to regret that relationship passionately, and it is impossible to consider her work without reference to its impact on her art and life.

She apprenticed herself to the future pioneer of abstraction in 1902, when she enrolled at age 26 in his evening life-drawing class at the Phalanx School, which he had just opened in Munich. "There and then I had a new artistic experience," she is often quoted as saying, "how--unlike other teachers--Kandinsky explained things in detail, clearly, and treated me as though I were a consciously striving person who can set herself problems and goals. That was something new for me and it impressed me."[3] Her astonishment at being taken seriously, with all due respect to Kandinsky's pedagogical skills, is poignant testimony both to the inadequacy of her earlier training (barred from the art academies on account of her sex, Munter resorted to lessons from private tutors and ladies' art associations) and to the then prevailing contempt for women artists. In the exhibition catalogue, Heller describes the misogynist forces that worked to discourage women's artistic aspirations, citing, for example, the art critic Karl Scheffler in 1908: Since woman cannot be original, she can only attach herself to men's art. She is the imitatrix par excellence, the empathizer who sentimentalizes and disguises manly art forms. In Goethe's words, she "is not capable of a single idea" and "takes the knowledge and experience of man as ready-made and adorns herself with it." She is the born dilettante.[4]

Widely read art magazines such as Jugend and Simplicissimus likewise ridiculed women artists, and in this context Munter's persistence seems additionally impressive. Finding a sympathetic mentor in Kandinsky, she pinned her hopes on him. Eleven years her senior, he may well have been a parental surrogate--Munter's father had died when she was nine, her mother when she was 20. The ensuing saga is well known: within a short time, Kandinsky, though married, pressed his student for a romance; by the summer of 1903, they were secretly engaged, pending his divorce. Fourteen years later, Munter was still waiting for him to fulfill his commitment when he abandoned her to marry another woman. As revealed in Heller's biographical chronology, a veritable page-turner incorporating heartfelt letters and diary entries, Kandinsky did not conduct himself nobly in this affair. He even neglected to tell her when it was over. After the war, he stopped writing to her from Russia, ignoring her efforts to contact him, and she learned secondhand of his marriage to Nina von Andreevskaya. His behavior was duplicitous, confused at best, and Munter suffered from it bitterly.

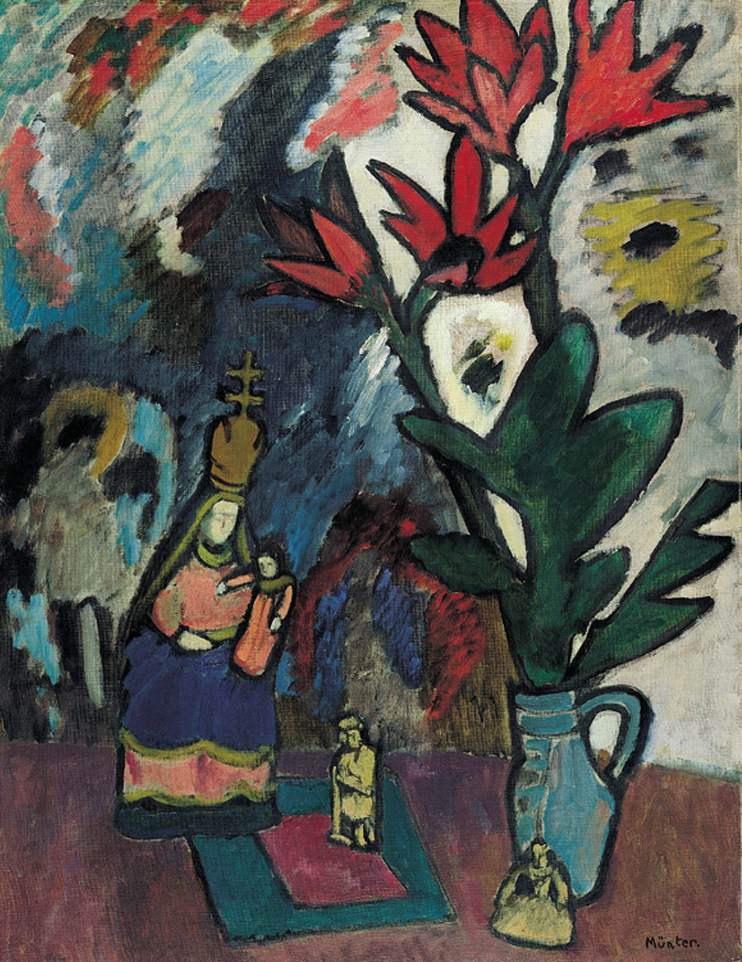

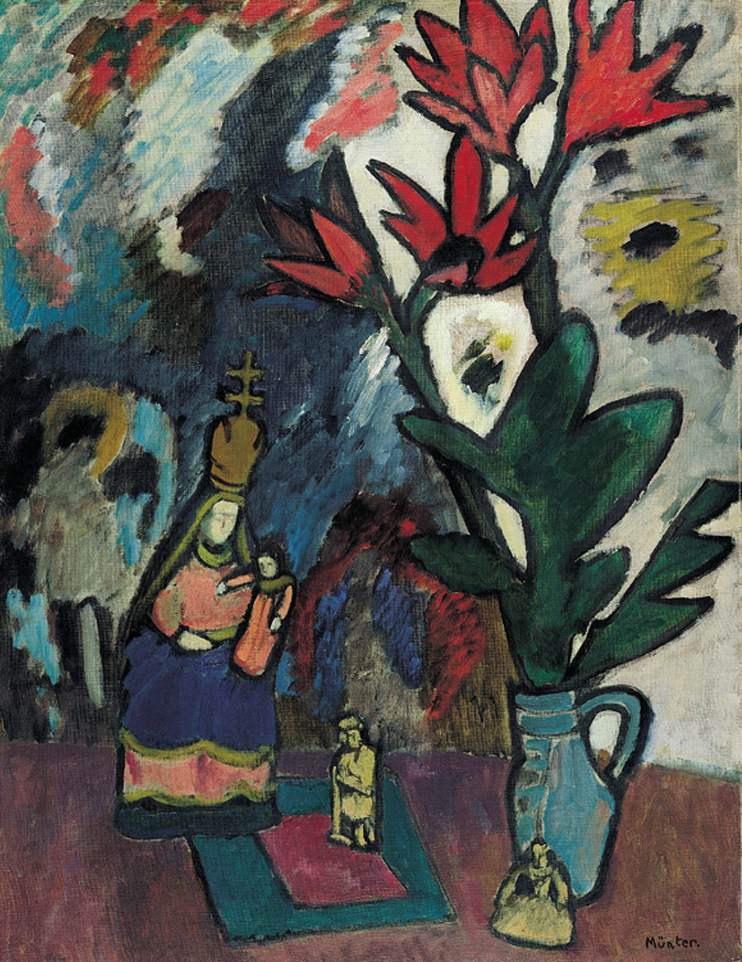

Gabriele MÜNTER,

Madonne et poinsettia, 1911, 92,5 X 70,5

During the time they were together, Munter assisted at the founding of the New Artists' Association and the Blue Rider, traveled extensively with Kandinsky, and bought a country retreat for the two of them in. Murnau, in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. It was here, in the stimulating company of their artist friends Alexei Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, that Munter truly hit her stride as a painter. "I took a major leap," she wrote, "from painting after nature, more or less impressionistically, to the feeling of a content to abstracting to the presentation of an extract."[5] Jawlensky in particular seems to have served as a catalyst; he had assimilated the principles of French Synthetism, and one sees them transmitted to Munter in works like her Girl with Doll (1908-09), where broad planes of bright color, often thinned to near translucency, are outlined in black, producing an effect akin to stained glass or cloisonne enamel. In Murnau, too, Munter began to collect and emulate the folk art of Hinterglasmalerei, or reverse-glass painting, and Kandinsky followed her lead, adopting the technique in his own work and reproducing a number of 19th-century examples in the Blue Rider Almanac.[6]

It is a pity that the exhibition does not include any of Munter's reverse-glass pictures, nor any of the fascinating, careful studies she made after children's drawings, which she and Kandinsky also collected.[7] But a selection of color lino- and woodcuts does show her radically simplifying and distilling imagery while mastering a new medium. She produced the first of these prints, tiny portraits and street scenes, during a sojourn with Kandinsky in Sevres, and exhibited them in Paris before returning to Germany in 1907. Heller discusses them in detail, and just as Peg Weiss identified the critical role of graphic art in Kandinsky's formal development,[8] Heller sees Munter's most progressive stylistic tendencies emerging first in her prints. Several from 1908 depict little girls and their toys, an unsurprising choice of subject given Expressionism's inheritance of the romantic cult of the child, yet Munter's approach seems uniquely affectionate and familial, unlike the prurient interest taken by Brucke artists, for example, in their young models. The blond girl in the tender Sleeping Child is Munter's niece Elfriede Schroeter. In the artist's attention to her, and to her cousin Annemarie Munter, it is tempting to detect a young woman's dream of the daughters she would never have.

Her situation was complex. Social expectations dictated for Munter a home and a family, but her independent turn of mind, reflected in her decision to become an artist, deflected her from these goals--apparently not without emotional conflict. She desired marriage from Kandinsky, to be sure, but could her choice of such an unavailable mate have been an unconscious strategy for ensuring her autonomy? Subtle patterns in her decidedly nonnarrative, nonsymbolic pictures hint at her ambivalent feelings. In the idyllic retreat she established in Murnau, she could enjoy the periods of blissful domesticity celebrated in paintings like Country Homes (Kandinsky in the Garden), 1912, and Interior (Still Life, Bedroom), 1909. In the latter, Munter presents a pleasant room with cupboards, washstand and, glimpsed through an open doorway, Kandinsky comfortably reading in bed. Oddly, however, the strong welcoming diagonal of a rag rug does not lead to him but veers away from the bedroom altogether and dead-ends in a corner. Pentimenti record the shifting position of the rug on the hardwood floor and betray the artist's own indecision. A favorite compositional device similarly suggests reservations (or regret?) with regard to the tempting security of home, as Munter moved about with Kandinsky from hotels to rented rooms. In images of houses such as Fall Evening--Sevres (1907), Rose Garden (ca. 1907-08), Oberau (1908), The Pink House (Country Home near Murnau), 1908, and House in Winter (1909), she deploys assertive foreground horizontals that bar access to the home. Formally, these fences or low walls serve as effective repoussoir elements ; on a symbolic level, they may externalize feelings of frustration, alienation or defense.

Another of Munter's telling compositional devices is the vertiginously receding road, seen in the linocut Path (1907) and the oil-on-cardboard Country Road in Winter (1909), where solitary figures traverse lonely avenues that wind into the distance. Seen from the rear, these small, burdened figures lean on walking sticks; like Munter, they go their independent ways along routes that direct them away from the safe houses ensconced behind protective stone walls. Even before she met Kandinsky, Munter herself was a seasoned traveler, and one of the great surprises of the exhibition catalogue is an album of sketches and photographs she made during her American tour, 1898-1900. Visiting relatives in Missouri, Arkansas and Texas, she participated in cattle drives and cowboy reunions, saw the St. Louis Exposition and made excursions to the Mississippi and Niagara Falls. Although there is little residue of this extended voyage evident in the works in the exhibition--except for the rare still-life motifs of an Uncle Sam doll and an American flag--Heller suggests that the trip was fundamental to Munter's artistic development, fostering a sense of self-reliance. And yet, strong as she must have been, she was haunted by self-doubt. Internalizing the prevalent negative judgments about women's ability to make art, she constantly sought reassurance from Kandinsky, worrying, for instance, about her tendency to paint "in a variety of ways," confiding that often her works seemed "too different from one another.[9]

In this she was certainly correct, for she was unable always to sustain her bold Expressionist vocabulary and retreated from time to time to a conservative naturalism, as in the searching Self-Portrait in Front of an Easel (ca. 1909) or the slightly later portrait of Kandinsky's mother, Lydia Kojevnikoff. One senses that such stylistic relapses correspond to moments of psychological duress. Muller painted the latter of these two portraits, for instance, when the Russian matriarch "visited her son, his first wife, and his `fiancee' in the spring of 1913 in Munich and Murnau."[10] The unsmiling, suspicious look delivered by Kojevnikoff suggests a formidable, even intimidating presence. Munter articulated the strong but sagging features respectfully, ending with a conventional image of Mutti far less daring than her portraits of Jawlensky (1909), Olga Hartmann (1910) or the stunning, Matisse-inspired Portrait of a Young Polish Woman (1909). And when confronting her own image in the mirror, faced with the task of declaring her identity as an artist, Munter armored herself with traditional props--easel, palette, brushes, flowered hat--and modeled her face in a kind of labored late Impressionism at odds with the much more quickly executed and "unfinished" quality of the rest of the canvas.

Her experiments with abstraction a la Kandinsky, undertaken during the teens, are similarly unsatisfying, and show her working dutifully against her established strengths. Although she exhibited regularly in Germany and abroad, it is hard not to conclude that insufficient affirmation of her own powers and considerable accomplishments deprived her of the kind of confidence exuded by her male colleagues. As Heller points out, both Kandinsky and Johannes Eichner, the companion of her later years who published and promoted her work, constructed her as a "natural" talent, and thus outside the cultural and intellectual discourses that confer meaning. After her separation from Kandinsky, Munter recanted her remarks on the quality of his instruction, recalling how he had declared her "hopeless" as a student and had insisted he "could teach [her] nothing."[11] To what degree did she believe his assessment? The question, like the larger Frauenfrage hotly debated in Germany at the time, is critical to an understanding of Munter's achievement, and any responsible accounting of her contributions must, as Anne Wagner insists, take "both public and private representations and estimations of women's place in art among the determinants both of the artist's self, and of her art."[12]

Munter's most ambitious and memorable painting remains the large-scale (49 1/4-by-28 7/8-inch) multifigure portrait Boating (1910), which depicts a summer outing on the Staffelsee near Murnau. Kandinsky stands handsomely in the stern of the boat, framed against the blue mountain landscape and dominating the seated group, including, with her back to the viewer, Munter at the oars. Werefkin, in her big red hat and powder blue dress, is joined by a black dog, and next to her a child sits primly, with hands folded in his lap. This boy, Andreas Jawlensky, born in 1902, did not belong to Werefkin but to her young Russian maid, Helene Nesnakomoff. In the painting, Munter manages to capture a certain diffidence between Werefkin and the child, whom she accepted as Jawlensky's son but did not warmly embrace. Proud of her platonic love for Jawlensky, four years her junior, Werefkin had given up painting to further his career. She moved to Munich with him and supported him and their household financially until the Russian Revolution halted her income. He left her after the war, marrying Nesnakomoff and finally acknowledging his son, whom he had until then called nephew.[13] Munter and Werefkin thus had in common ultimate betrayal by the men they loved, but the tensions that riddled the respective relationships of these artist-couples are hardly apparent in the lovely Boating, where the triangular mass of figures promises enduring stability and the serene lake is yet unruffled by winds descending from the artist's brooding purple sky.

Sue TAYLOR, « Gabriele Münter : Espoused to Art - German Expressionist painter », Art in America, janvier 1999

NOTES

[1.] My allusion, of course, is to Carol Duncan, "Virility and Domination in Early 20th-Century Vanguard Painting," Artforum, December 1973, pp. 30-39.

[2.] Reinhold Heller, Gabriele Munter: The Years of Expressionism, 1903-1920, New York and Munich, Prestel-Verlag, 1997.

[3.] Gabriele Munter, quoted in Heller, p. 12.

[4]. Karl Scheffler, quoted in Heller, p. 46.

[5.] Munter, quoted in Heller, p. 16.

[6.] See the invaluable documentary edition of Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, eds., The Blaue Reiter Almanac, ed. and trans. Klaus Lankheit, New York, Viking Press, 1974, repr. Da Capo Press, 1989.

[7.] Three oil-on-cardboard copies by Munter of children's crayon drawings of houses are reproduced alongside the delightful originals by Jonathan Fineberg in The Innocent Eye : Children's Art and the Modern Artist, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1997, pp. 70-71, figs. 3.45-50.

[8.] "Graphic art in particular, which required above all simplification, reduction, and compression of imagery, afforded [Kandinsky] the necessary bridge between ornamentation and abstraction. It was in graphic art that drastic transformations were first undertaken and here that Kandinsky found his way to abstraction." Peg Weiss, Kandinsky: The Formative Munich Years, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 135.

[9.] Munter, quoted in Heller, pp. 155, 156.

[10.] Heller, p. 122.

[11.] Munter, quoted in Heller, p. 27.

[12.] Anne M. Wagner, quoted in Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron, eds., "Introduction," Significant Others : Creativity and Intimate Partnership, London, Thames and Hudson, 1993, p. 12. For further discussion of the "Woman Question" and its implications for female artists, see Rosemary Betterton, "Maternal Figures: The Maternal Nude in the Work of Kathe Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn Becker," in Griselda Pollock, ed., Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts : Feminist Readings, New York, Routledge, 1996, p. 164.

[13.] See the excerpts from Werefkin's diaries in Mara R. Witzling, ed., Voicing Our Visions : Writings by Women Artists, New York, Universe, 1991, pp. 17-46.

"Gabriele Munter: The Years of Expressionism, 1903-1920" was organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, where it appeared [Dec. 5, 1997-Mar. 1, 1998] before traveling to the Columbus Museum of Art [Apr. 18-June 21, 1998] and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond [July 13-Sept. 20, 1998]. The exhibition is now on view at the Marion Koagler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio [through Jan. 3].

Author: Sue Taylor is an assistant professor of art history at Portland State University, Portland, Ore.

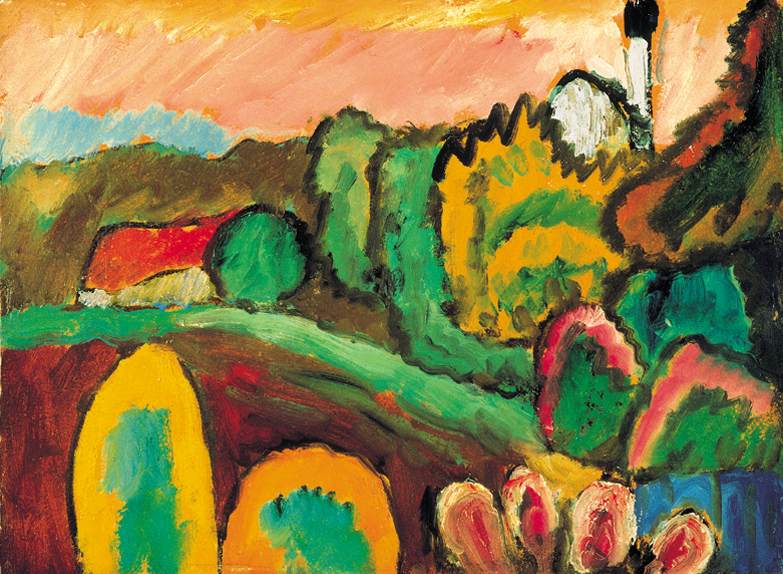

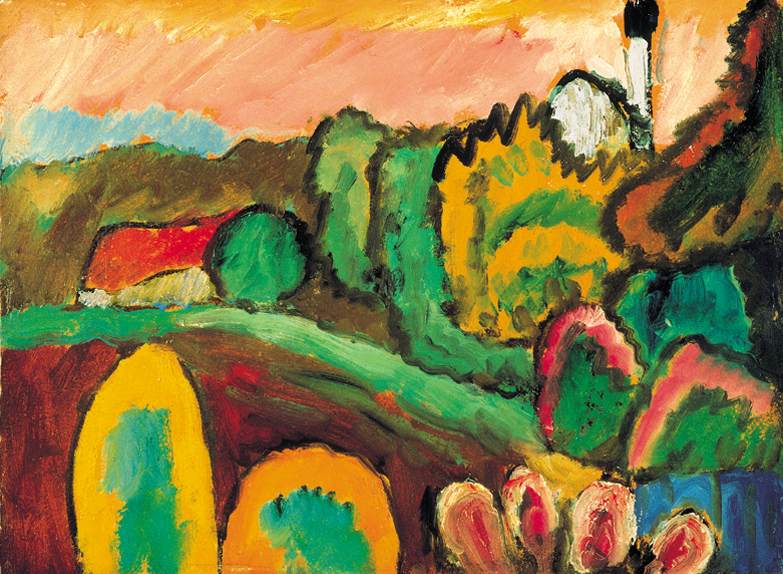

Gabriele MÜNTER,

Vue avec église, 1910, 33 X 44,8

Much can made of the fact that too little attention has been paid to Gabriele Munter, one of the only significant female participants in German Expressionism. As a young woman, Munter, who was born in 1877 in Berlin, was a founding artist member of the Neue Kunstlervereinigung (New Artists' Society) in Munich in 1909 and the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group in December 1911. But for most of us she has remained largely defined by her teacher/acolyte relationship with Wassily Kandinsky. It was a professional and personal relationship that in many ways paralleled that of Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin. Munter's dual role as Kandinsky's student and eventually the betrayed mistress of the married artist turned out to be personally traumatic, as well as both good and bad for her work as an artist.

There is no question that Munter's work now needs to be re-evaluated in a context that takes into account recent feminist consciousness. Thus, this traveling exhibition, which began in Milwaukee in 1997 and has toured the United States, should and could have raised our contemporary awareness of a new, re-examined Gabriele, in light of, if not feminist theory, then at least of an awareness of the specific circumstances that circumscribed her art.

While her paintings, prints, and drawings certainly emit a strong visual appeal more than seventy years after they were made, the traveling show of eighty-two works lacked the animating tension and fresh interpretation that could have made this a very good exhibition indeed. Unfortunately, it broke no new ground. Instead, it essentially rehashed what has already been known about Munter for a U.S. audience.

In the catalogue preface, Milwaukee Art Museum director Russell Bowman claims the exhibition merits significance simply because his museum is the steward of one of the most comprehensive collections of German art in the United States. (It is interesting that Milwaukee's eleven Munter paintings constitute the largest cache of her work outside Germany, as well as the largest in a single U.S. museum.) According to Bowman, the most prominent motive for mounting the exhibition appears to have been "to offer an American audience an in-depth view of Munter's extraordinary achievement" (7). The guest curator, Reinhold Heller, professor of art history at the University of Chicago, states that his exhibition is similar in scope to a comprehensive 1992 exhibition of Munter's work organized by Annegret Holberg at the Stadtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich (8). But he does not describe the ways in which his exhibition is similar to the Munich show, nor does he explain why he would want to imitate it.

Hung chronologically, the exhibition charts Munter's stylistic development from a student into a fully mature artist. (No work after 1920 is included.) All in all, the chronological hanging of the exhibition made the whole scenario seem a little too smug. Perhaps a more effective strategy would have been to group the show thematically, even within a chronological format, especially since the artist's early work depicts the domestic subjects of a woman's world (consider, for example, two color linoleum cuts : Child with Bottle and Washing at the Shore, both ca. 1907-8). The influence of male artists on her development also could have been examined. (Her 1909 oil on cardboard, Still Life, Bedroom, possesses an uncanny resemblance to Vincent van Gogh's painting of his bedroom in Arles; Kandinsky's influence on Munter's improvisational abstractions is unmistakable and is discussed at length in the catalogue.)

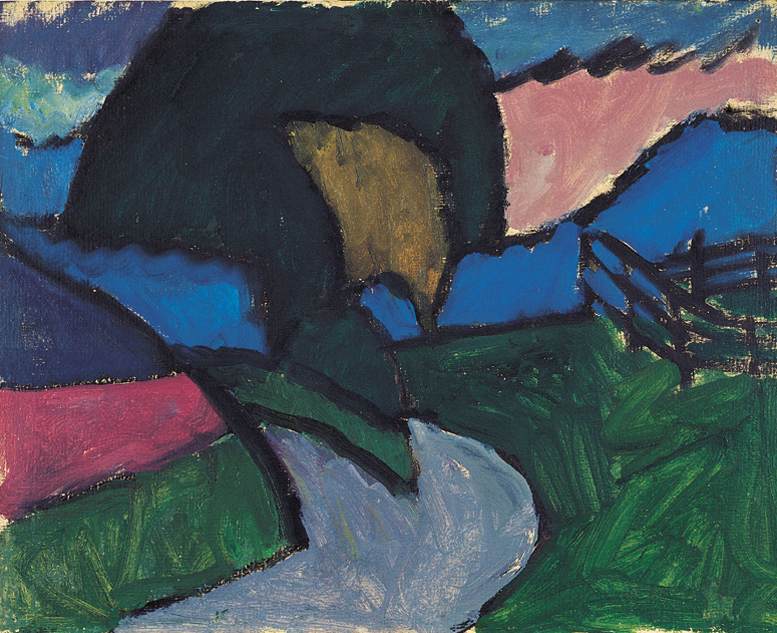

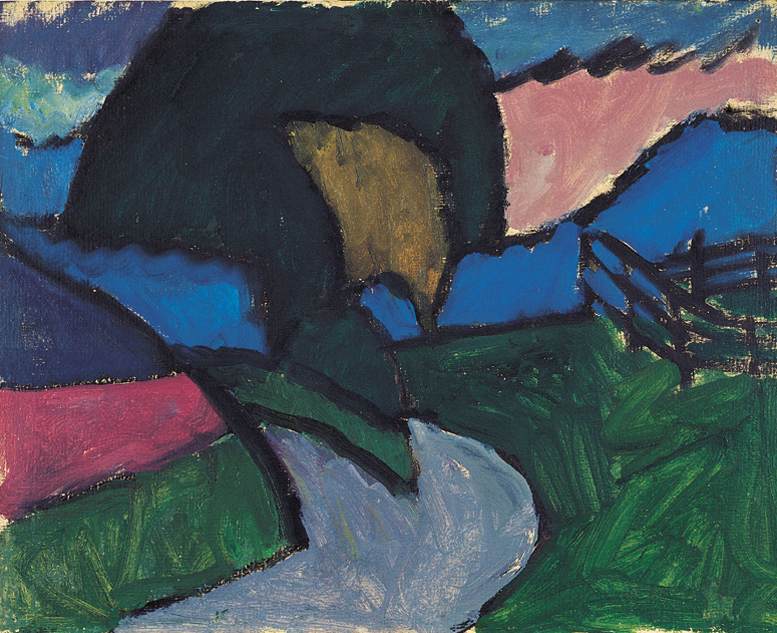

Gabriee MÜNTER,

Paysage d'automne, 1910, 32,8 X 40,6

The story of Munter's life appears in retrospect to be a classic and formative tale of female dependence, seduction, and betrayal. Though her early years in the United States developed her sense of self-reliance and independence and reinforced her ability to override external authority, her relationship with Kandinsky impeded her mature artistic career. In 1904, she became his mistress and his apprentice and collaborator, even sharing his palette. But even early on, Munter's work appears more austere, harmonious, and attentive to the significance of the mundane than that of her mentor. Kandinsky actually left his wife for her and promised to marry her after they began living together. But, breaking his vows, he never made good on his promise of marriage, and in 1915 he visited her only briefly in Stockholm, where he had fled to sit out World War I, only returning to Germany late in 1920. By 1921, they had formally broken all contact with one another. A property settlement was not reached until five years later. In her manuscript, "Confession and Accusation," written between 1925 and 1928, Munter vented her bitterness: "I allowed myself to be lied to and cheated out of my life. . . . And now I think that even what I gained from him as an artist was only half only a small quarter nothing complete, no totality" (27). The rest of the story is a postlude: by 1929 Munter had formed an apparently happy liaison with the journalist and art historian Johannes Eichner that lasted until he died in 1958. She continued to paint, embarking on a series of pictures depicting the Nazi highway project, the Olympiastrasse, in 1936; later the Nazis denounced her work. She secreted her collection of Blue Rider works in the cellar of her house in Murnau, hiding them first from the Nazis, then from the U.S. occupying troops. She never left Germany during World War II. (While she continued to make art, it is clearly the work of her early years that has earned her an art historical place.) After the war, she was rediscovered, and celebrated, as one of the few surviving members of the Blue Rider group. She died in Murnau in 1962 when she was eighty-five, a year after her first U.S. exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles galleries.

In the exhibition and even the catalogue increased analytical attention should have been paid to the significant cause and effect that the circumstances of Munter's life had on her work. It seems no accident that she evolved beyond expressionist and abstract styles while she was living in Stockholm during World War I. It was there, increasingly detached from Kandinsky's influence, that she loosened her style. (This occurred while Kandinsky was in Russia, waiting out the war himself.) The exhibition's penultimate piece is the lovely Street in Stockholm (May Evening in Stockholm) (1916), in which (in this context) a born-again woman is symbolically emerging through a fallopian tube/portico into the bright life of life. It is followed by The Future (Woman in Stockholm) (1917).

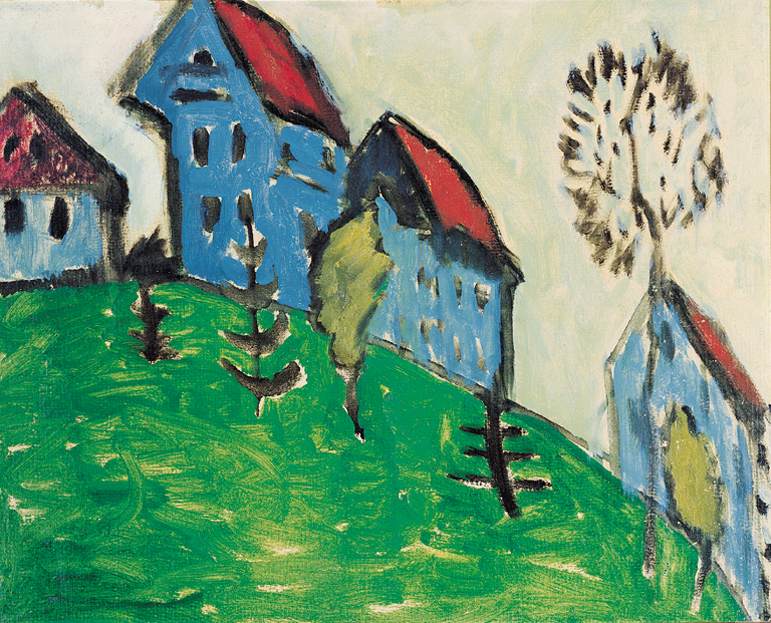

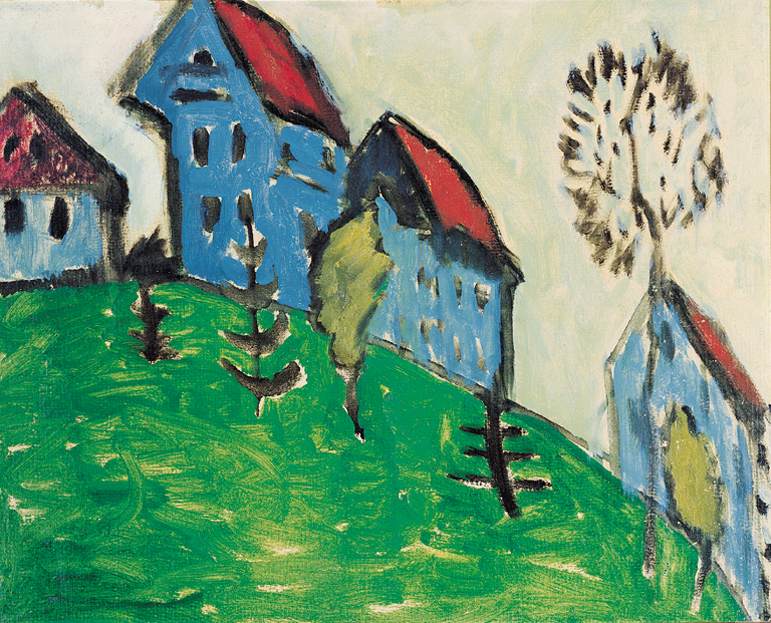

Gabriele MÜNTER,

Village sur la colline, 1911, 33 X 40,5

Assuming that since 1992 there have been no significant Munter scholarly controversies, the exhibition could have used a sociological orientation to lend it additional complexity and depth. The catalogue, admirably researched and, happily, written without Clusters of footnotes, serves its general purpose well. It contains interesting though rather oblique discussions of the coherence of an individual artist's stylistic plurality and of the importance of the figure for Munter in the face of abstraction. There are stimulating discussions of especially the Murnau paintings, of the nature of her relationship with Kandinsky, and of the Phalanx group, which, by implication, relates to guerrilla exhibitions in alternative spaces as well as the fact that the conservative German art academies that excluded women. It is instructive to be reminded again that at the turn of century women could not study in the art academies; their creative abilities often were denigrated and subject to public ridicule. But, just as with the better-safe-than-sorry hanging, the catalogue's trajectory never departs from the linear, though it is interspersed with a few intriguing eddies of thematic thought.

Nevertheless, almost a century after it was made, Munter's early work holds up visually, unlike that of some of her male contemporaries. In spite of her romantic unhappiness, she lived a full artistic life, participating in modern art's energetic years between the wars, and she left a rich legacy to which this exhibition admirably attests. The enduring impression of this exhibition is one of unfulfilled expectations. A more explicit effort to articulate Munter's role as a female pioneer would have been appreciated. Without it, much of the drama and reality of her achievement and her life continue to remain invisible.

James SCARBOROUGH, « Gabriele Münter: The Years of Expressionism, 1913-1920 - Review », Art Journal, Spring 1999

Compte rendu de :

Reinhold Heller. Gabriele Münter: The Years of Expressionism 1913-1920, Munich : Prestel-Verlag, 1998. 208 pp.

Exh. cat. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1997. (Exhibition schedule: Milwaukee Art Museum, December 1, 1997-March l, 1998 ; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio, April 18-June 21, 1998 ; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, July 13-September 20, 1998 ; Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, November 3, 1998-January 5, 1999).

Gabriele MÜNTER (1877-1962)

Gabriele MÜNTER (1877-1962)